by Cody Poulton

I thought I was a citizen of the world, but today borders matter more than ever, and I’ve come around to thinking, in spite of myself, that it’s a good thing we have them. We’ve all erected barriers to protect ourselves from Covid-19, but if we’ve learned anything during this pandemic, it is that the final border is our own skin, and even that is permeable. We share the air.

To avoid cancelling the Tokyo Olympics in 2020, Japan was slow to impose a shutdown, then moved rather quickly to restrict entrance for foreigners—something it’s been very good at when it wants to for more than a millennium. This is a story of how I managed to sneak back into the country during the pandemic and where that presently leaves me now.

I hold a resident card for Japan, and I risked losing that status had I remained in Canada. Some years ago, not long after 9/11, I’d made the mistake of overstaying my ninety-day tourist visa for Japan and had very nearly been deported. I was instructed to go to the Ibaraki Immigration Management Center, located halfway up a mountain somewhere between Kyoto and Osaka. The place was in fact a detention center. A guard waved us in at the gate. Inside, a friendly man in uniform pulled out a flow chart to show me where I was in the system and what hoops I had to jump through to avoid detention and deportation. I was told to return at a later date with the following four documents: an alien registration card; a copy of my Japanese wife’s family registry, a document certifying our marriage; and an essay explaining why I should be allowed to remain in Japan. As we left, I said to the cabbie, “I get the impression it’s a lot easier to enter that place than leave it,” and he said, “You got that right, brother. Most of the time I take couples up and they’re laughing on the way there, but only one on the ride back and she’d be looking pretty glum.” I replied, “You don’t know my wife. She’d be either laughing on the way back too, or cursing up a storm, depending on how she feels about me at the time. Shonbori (glum) isn’t her style.”

Eventually it took three trips up and down the mountain before I was let off probation. A revelation of this exercise was discovering that I’m listed as an adopted husband on my wife’s family registry. Without telling me, Mitsuko had entered me in the family registry under her own name. That is to say, in the name of her ex-husband, which, for her children’s sake, she had never changed. In any case, this may have saved my bacon. I got my alien registration card, though I failed to see the purpose of it if I was there illegally. In the little box describing my qualifications for being in the country was entered the word, “none.” I rather wish I could have kept that, but I had to surrender the card when I left Japan. In any case, this taught me the lesson that I was better off applying for a spousal visa, which gives me a residence card. I have to renew it every three years, but it lets me come and go as I please. My wife was declared a landed immigrant in Canada after we were married, but the regulations changed after 9/11, Who had the right to live in another country got tighter, she has had to reapply every five years for a new Permanent Resident Card. That is to say, she may be a permanent resident, but her card isn’t.

Two summers ago, our return to Kyoto in time for O-Bon (the annual feast of the dead) was inspired less by the need to mourn the dearly departed than to justify our right to live in each other’s countries. I had to renew my resident card and by a wicked synchronicity Mitsuko had to renew her permanent residence card too that year. Citizenship and Immigration Canada dragged their feet for months before sending notice that her application had been accepted, but we had no time to pick up her card in Vancouver before we had to return to Japan in order for me to renew my own card before it lapsed in September. That we left the country without her new card would cause us both untold trouble and a good deal of money. It was ironic that the process of my renewing my residence status in Japan was considerably easier and cheaper than it was for my wife to renew her permanent residence in Canada, supposedly a nation of immigrants. As for why it’s easier for me to renew my own resident status in Japan, perhaps the reason is that there are fewer of my kind here.

I filed my own application at the immigration office in Kyoto with a sheaf of documents from the ward office. As a reason for requesting the renewal I mentioned the three children and seven grandchildren here (one can’t go wrong pressing the Confucius button) and made up some blather about wanting to bury my bones in Toribeyama, Kyoto’s oldest graveyard. I thought I was covered, but was given further instructions to provide them with sufficient evidence that, should I retire to Kyoto, I would not present myself as a burden to the state. I realized I was asking Japan to import precisely what they have a surfeit of: yet another senior.

No sooner had we returned to the house than I caught the pungent odour of incense and knew that Michiko was praying to grandma that our paperwork would proceed smoothly. She was then on the phone to complain that trucks passing in front were making our house shake due to the potholes left by the city water people. “I swear to you, if another truck lumbers past our door, the place will collapse over our heads,” she said. Less than an hour later a truck arrived, loaded with asphalt and two young men, their faces and arms black as charcoal from working all day in the sun. Kyoto in August is a blast furnace, but there they were, with a blowtorch to soften the asphalt for shovelling. In what other country would the city send workmen to fill your potholes at an hour’s notice? And who but my wife could prevail on them to do so? She was outside, giving the boys directions, remarking that roadwork always fascinated her and that, hell, if they had a spare shovel she’d pitch in too. (Later, over dinner, the women embarked on a shinasadame of the masculine beauty of road workers, a female version of Genji and his buddies’ appraisal of girls on a rainy night.)

By morning I had all the documents—god bless konbini, Japanese convenience stores, where you can print anything anytime off a USB stick—and we headed back across town to the immigration office. Documents duly submitted, we had time to pay our respects to granny at the Otani Mausoleum, over by said Toribeyama. When we got there, we found the parking lot closed for O-Bon. Mitchan, a take-charge sort of girl, told the parking attendant her daughter worked there. (The truth is that a neighbour works in the restaurant.) They called and quickly permission was granted to park there like we were VIPs. First, we went to see Ms. Ono, who runs the shop selling flowers and incense for the graves. From the ceiling of her shop hang tin buckets dating back to the Meiji era, used for washing the graves, and behind her there are cubbyholes in the wall for boxes of incense. Both buckets and boxes bear the names of old Kyoto families. The lady knows them all and is one of my favourite people here. I’ve been going there with Mitsuko at least a couple of times a year for the last twenty, and she always makes a point to chat with us. The whole family was out selling flowers and incense. Merchant Mitchan, always with an eye on the buck, remarked that O-Bon is big time for bonzes to rake in the cash and who could argue with that? “You must be busy too,” we say to Ms. Ono. “Yes, but you know, the population is getting smaller. Fewer and fewer are coming every year.” As Japan’s dead increase and fewer are being born, there are fewer left to mourn—now that is a sad thought.

Our prayers to granny completed, we went back for more flowers and incense for the grave of Mitsuko’s ex’s grandfather, somebody who was a big name in his time. At New Year’s, celebrities like the kabuki actor Nakamura Ganjirō would pay respects at his shop, and his wife, seated by his side at the entrance smoking her long pipe, would pass out packets of money to everyone. Washing the Ohara grave is a ritual at which I always feel superfluous, but maybe I should be thanking the patriarch for granting me the privilege of being able to stay in Japan? At least the grave is located just a few steps up the hill, because it was blistering hot. My wife commiserated with a couple of young women there to wash their family graves, wilting in formal kimono. Task accomplished, it was lunchtime. The prospect of death makes the living hungry, so we headed to our friend’s restaurant, located in the basement under the main reception area of the Otani Mausoleum, thus justifying the free parking with an excellent tempura lunch.

My wife was stranded in Japan until the Canadian embassy in Manila—Tokyo no longer has visa services—could issue her with a special re-entry visa and, some weeks later, we made a trip over to Citizenship and Immigration’s office in Vancouver to get a lecture about how my wife had been abusing her marital status by spending so much time in Japan. “Just being with a Canadian in Japan isn’t equivalent to living in Canada, you know,” she said. “If you become a Canadian citizen, that’s the end of your problem.” My wife is reluctant to do that because, so far, Japan doesn’t recognize dual citizenship.

She was due to return to Japan on St. Patrick’s Day last year, just after the WHO declared the global pandemic. I made sure she cancelled her plans because I didn’t relish the idea of our being separated for an indefinite amount of time. We rode out the pest for the following few months in British Columbia, where we live most of the time, but in September the Japanese government announced they were relaxing the regulations preventing people like me, spouses of Japanese nationals, from entering the country. For months, thousands of residents of Japan who are not Japanese citizens were stranded outside the country. It had become a human rights issue before the government buckled to pressure from foreign governments, chambers of commerce, media. The truth is, Japan needs its foreign workers. Since I was working remotely like many others, it made little difference where I was actually living, so I quickly made plans for the two of us to return to Japan. Domestic transfers were not permitted, and everyone coming back was obliged to quarantine for two weeks on arrival. As a non-Japanese, I was required to get a special re-entry permit from the Japanese consulate and also had to test negative for covid 72 hours prior to departure from Canada.

The journey over in a Boeing Dreamliner had more cabin crew than passengers. We arrived at Narita at 2:30 pm and quickly deplaned. There followed a scavenger hunt down long corridors and sundry waiting rooms as officials checked and double-checked, then triple-checked our forms and gave us more to fill or hold, but I received no snakes-and-ladders chart—I had heard that if you could not produce the right forms, you would Go Directly to Jail. We were given saliva tests in little cubicles posted with photos of juicy pickled plums and lemons to inspire Pavlovian salivation. My wife complained loudly in her inimitable Kyoto dialect that she couldn’t fill the test tube with enough spit, eliciting good-natured laughter from the quarantine folks. We were subsequently split up as my test results came in earlier than hers. Negative again, twice-blessed, I was told to proceed to Immigration, where my documents were checked, then double-checked by a second official, and I was officially let loose into the baggage check area, Mitsuko happily following on my heels. A friendly beagle sniffed our bags and gave us leave to take them to Customs.

It took us ninety minutes to clear everything. There followed the long ride into town on the “Corona taxi” with a chatty driver who’d lived many years in Seattle and still had one daughter there. (Another is a singer with her own TV program in Riga, Lithuania.) We passed the time comparing Naruse Mikio’s women to those in Mizoguchi’s films, Mishima’s decadence over Dazai Osamu’s, the pleasures of hiking in the mountains, the theory that the Japanese are one of the lost tribes of Israel.… At Hamadayama, we checked into the cellphone shop to activate our phones because, since Covid, the company has closed their kiosk at Narita.

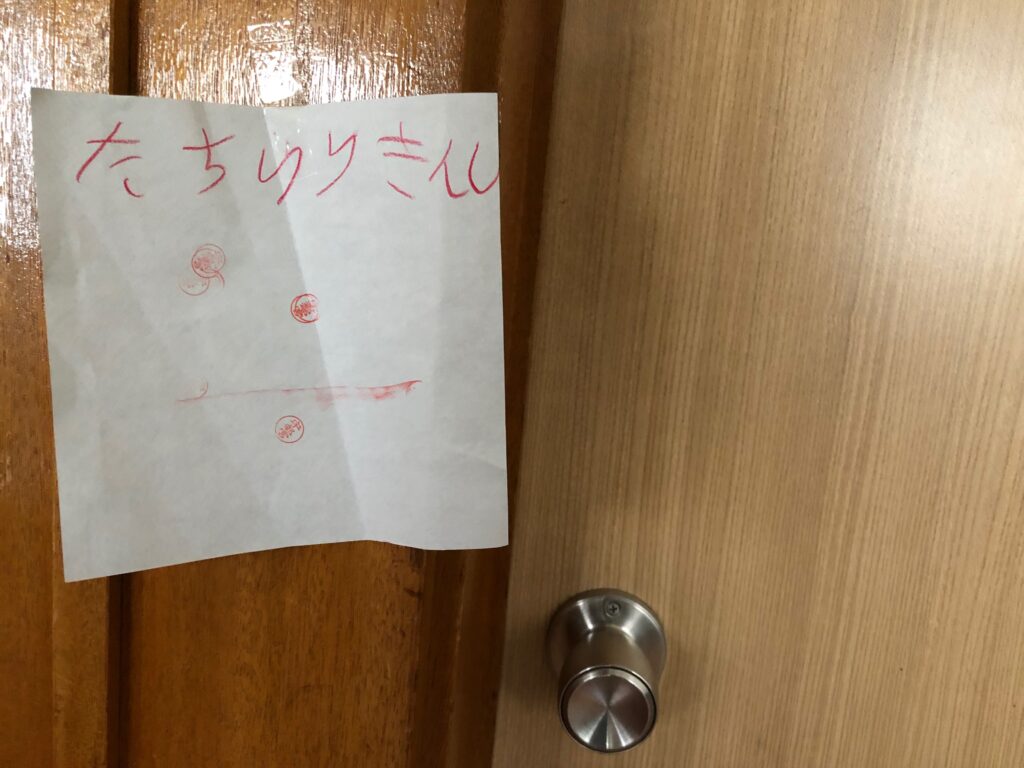

We encountered a preponderance of lefties that first day: left-handed quarantine officer, another one at immigration, a southpaw girl in the cellphone store—encouraging signs of a growing non-conformity in this country. We finally reached our daughter’s place around seven pm, to a hot bath, cold beer, gyoza, and an early bed in the spare room upstairs. Yayoi’s study was to be taken over by the grandparents as in Ozu’s Tokyo Story, only the desk hadn’t been moved into the hallway. She had posted a sign on her door, written in crabby hiragana, tachiiri kinshi (no entry), and stamped it in red all over with the family chop to make it official, but she was gracious enough to lend her private space to us.

The quarantine in Japan was a soft one. People are allowed out to go for walks and do their shopping. Only the Kyoto public health office contacted us, asking for an update on our health before we boarded the bullet train sixteen days later to return to Kyoto. One Sunday we walked into Kichijōji, a fashionable Tokyo neighbourhood. Inokashira Park was packed, as were the shops leading to the station, giving me a queasy sense of claustrophobia after the tranquility of Victoria.

One of our first orders of business when we got back to Kyoto last fall was going to the Otani Mausoleum to report our return to granny. The bus from Kawaramachi to the stop below Kiyomizu Temple is usually packed with tourists but this time was half empty. At the flower shop Ms. Ono told us a lot of places were going out of business, and we noticed on the walk back through Rokuhara the shutters down on a number of the guesthouses and restaurants catering to the tourist trade. That part of Kyoto indeed seemed like a ghost town, as if the dead were reclaiming the territory as their own. Gion was little better.

A deserted ‘happy Rokuhara’

But it was beautiful in Kyoto last fall. November here is always my favorite month, sunny and warm, and we spent whatever free time we had chasing maples, which is to say, on the hunt for autumn colours. The temple gardens were at their most photogenic and uncrowded. We almost felt we had the town to ourselves. The only tourists were the odd resident foreigner like myself (rare birds now) and other Japanese, taking advantage of the government’s Go To Travel campaign. This and the Go To Eat campaign have effectively served as super-spreaders of the virus. It would seem the government has valued economic stimulation over the lives of its citizens, but what’s new about that?

As I write this, it is spring in Kyoto and Japan has entered yet another wave of what seems like an endless pandemic. Covid cases and fatalities are higher than ever. Canada has made it even harder to return, our airline cancelling all flights from Tokyo to Vancouver for the foreseeable future. Everyone the world over is advising people to Stay Home, but I have to ask myself, where is that now? Since the New Year I have retired and in theory can live where I like, but I also find myself in a dubious battle with Service Canada to prove that I am in fact a Canadian resident in order to get my Old Age Security. Once again, a government seems to be forcing my hand. I have no plans of becoming a Japanese citizen. Donald Keene famously did, he said at the time, in solidarity with the Japanese people after the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Disasters do have a way of making choices where we live, but I rather think Keene had just grown tired of those long flights between Tokyo and New York. Eventually we all have to choose what the Japanese call their tsui no sumika, or final resting place. Maybe I wasn’t being so glib about wanting to be buried here.

*****************

For Cody’s piece on ‘Under Kiyomizu’, click here. For his runner-up prize winning piece for the WiK Competition in 2017, see here. To learn more about his work as professor of Japanese studies at University of Victoria, click here.

Recent Comments