by Cody Poulton

When I moved back to Kyoto in August I had to find somewhere to live for the long term. The old house in Katsura was no longer liveable; besides, I wanted to be closer to town. A friend of a friend, Mr. Fujita, was a real estate agent, so I asked him if he could find me a few places to look at. I told him my price range and roughly where I wanted to live. In a couple of days, he had three places lined up, so we met the next Saturday to see them. The first was an apartment in a condominium building, the second a machiya, or traditional townhouse, and the third was a three-bedroom house built sometime in the ’eighties not far from the river.

It was a blazingly hot day just before Obon, the festival when the spirits return from the dead to be entertained by their offspring. After three days, the spirits are sent home with bonfires on five of the surrounding mountains. If you can stand the heat, it’s one of the most beautiful of Kyoto’s annual festivals. Many try to find the roof of a taller building to witness the lighting of the okuribi, or “sending fires.”

We first visited the condominium apartment, which was located on the top floor of a high rise in the north of town. Though an older building, I was assured that it had been built after strict laws had been enforced to make tall structures like that safe in all but the most devastating of earthquakes. The apartment had been completely renovated, with new flooring and wallpaper and a new kitchen with an induction range. The only thing unchanged apparently was the toilet, from which issued a mouldy smell, which bothered me. Mould had been one of the things that had driven me out of our old house in Katsura.

The best part of the place, however, was the extraordinary view to the west, north, and east of the city. From the bedroom windows I could see four of the five mountains where they light the bonfires of Obon. To the west was Mt. Funaoka and Hidari Daimonji, and behind that Atago, Kyoto’s highest mountain; to the north, Takagamine and Kurama; to the northeast, Mt. Hiei; and east, Nyoigatake, otherwise known as Daimonjiyama. These mountains to the east and west are called Daimonji because the character for “big” (大) is traced out on their slopes. The outlines of a sail ship and the characters 妙法 (myōhō), meaning “wondrous dharma,” were inscribed on the sides of two other mountains to the north. A fifth mountain with the image of a torii gate was hidden behind a hill over to the northwest in Arashiyama. You could see it only if you lived over that way.

I thought to myself, what a great place to throw a party when they light up the mountains at Obon! But better yet was the effect when I opened all the windows. A refreshing breeze blew through, from west to east. One hardly needed the air conditioning. For most anyone in this city, which sits in a basin hemmed in by mountains, the summer is oppressively hot and humid and one can scarce survive it without the blast of an air conditioner.

The second place we saw was the machiya, which was located further to the north behind Imamiya Shrine. The place had been modernized with a new kitchen and bathroom, but it was hot upstairs and it was hemmed in by other houses. I imagined the downstairs would be dark and cold in the winter. The third place was a fine house, well built, but much too large for a single person like myself.

I could have asked the realtor to show me more places, but classes were beginning soon, I was sick of moving from one Air BNB to the next, and I was taken with the first place I’d seen. I am not one for making snap decisions, especially on first impressions, but I liked what I saw and knew I couldn’t find anything like it anyplace else. After a couple of weeks of negotiations and pieces of paper passing back and forth, the contract was sealed and I had the keys.

During the process I asked the realtor how long had it been on the market and he told me about a year. “So long?” I asked. Mr. Fujita replied that, at the cost of the rent, most people would prefer to put a down payment on a condominium rather than pay someone else’s mortgage. The rent was high by Kyoto standards, but half what it would cost me now to live in my own town back in Canada.

There followed calls to utility companies, purchases of bedding, a washing machine, a TV and other appliances. I finally moved in at the end of August. Until the first furniture arrived, I lived like a student, on the floor. Soon work swept me up in its rhythms. It would be a while before I would begin to feel settled there, but I loved the views and, just as expected, I hardly needed to turn the air conditioning on at all.

A month or so later a friend mentioned to me something called jiko bukken, or “accidental real estate.” I’d never heard the term before. She told me it referred to places where, most usually, someone had died, most often violently—a murder or suicide. There were directories of such places online, she said. It took me all of sixty seconds when I got home to find such a directory, and seconds more to zero in on my street address. Bingo! Jiko bukken! Dread. A click on the map opened a page with the apartment number. Thank god it wasn’t was my own unit, but it was, in fact, my neighbour’s. Someone called Hana-chan reported that a death had occurred there six years before. Moreover, it had happened outside, she wrote. It didn’t take much of an imagination to figure out it had been a jumper.

The next day I called Fujita and told him. He was terribly apologetic. “I was remiss in not doing a background check on the place before we proceeded to sign the contract,” he said. “I’d thoroughly understand if you’d want to move out, and I’ll do everything in my power to facilitate that.”

“Well, I’m not so sure I want to do that just yet,” I said.

“The landlord should have told us.”

I said it was my understanding in these matters that the ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ rule applied. It was the renter’s responsibility to do due diligence and ask about the place’s history and if we neglected to do so, the landlord was under no obligation to tell us.

“I can certainly negotiate some kind of deal with the landlord, though,” said Fujita. “Maybe a discount on the rent, or is there anything else you might want changed or repaired?”

I had already asked them to install an electrical outlet, which was strangely lacking in the new kitchen. “The toilet bothers me,” I said. “It’s clearly a hangover from the original place. It’s old and the ‘washlet’ isn’t very good.” Modern Japanese toilets are almost invariably furnished with a bidet with all sorts of controls to wash, dry, and warm your nether regions. This model was a good forty years old.

“I’ll see what I can do,” Fujita said. “If you’d like, I can also arrange an exorcism.”

An exorcism! Well, that is a strange offer, I thought. As much as out of anthropological curiosity than any fear of the supernatural, I took him up on his offer.

I had already been having certain misgivings about the place. Why had it been empty so long? Surely someone would have thought the gorgeous views, the space (at over eighty-five square metres, it was the largest apartment I’d ever seen in Japan), the renovations, would have appealed to someone in all that time. Even without this business of the suicide next door, however, I suspected that were my wife alive, she’d never have wanted to live there. One of bedrooms faced the northeast, the so-called kimon, or “devil’s gate.” Hence, the location for the Tendai temple Enryakuji, on top of Mt. Hiei, to protect the city from evil influences. At the very least, I should have got myself a nanten (nandina), typically planted in the northeast corner of a property to ward off evil.

Across the road from the northeast bedroom was a funeral parlour, and on the opposite side, southwest of the building, was a temple graveyard. At night I was awakened by the sirens of ambulances bearing the sick and injured to the local hospital. This was Kyoto, one couldn’t avoid such things, I thought, but then I fell ill, to one thing or another, and was hospitalized myself for a while.

After my wife died, I grew a beard. She had never liked beards. “Nothing good will ever come of a beard,” she used to say. I was beginning to consider shaving it off. Was it the beard or the bukken that was cursing me? And so I frittered away my fall. High time for an exorcism.

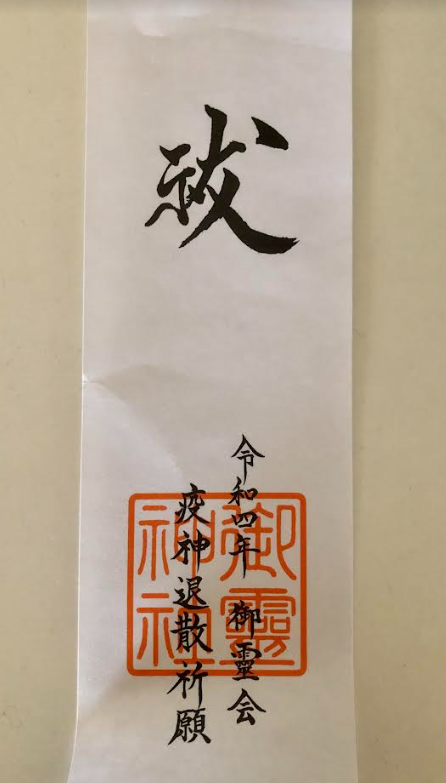

Fujita eventually got back to me. The landlord nixed the idea of replacing the full toilet but offered to replace the washlet. A workman came over the following week to take measurements and photographs. A date was set shortly before Christmas for the exorcism. He asked that I make sure I had a supply of rice, salt, and sake for the ritual. Water would be needed too, but tap water was fine.

On the appointed day, Fujita and the priest arrived with a lot of equipment that they had managed to cram into the elevator in one load. It consisted mostly of wooden frames and shelves for an altar, as well as stands for various offerings and tablets with the names of various gods, and sundry utensils in white porcelain. We pushed the dining room table into the kitchen to make way for the altar. Reed mats were laid on the floor as a base for it.

The priest himself was dressed in a green kariginu, literally “hunting robe,” over a white under-kimono. On his head he wore an eboshi court cap. This get-up made him look like Hikaru Genji, the hero of Murasaki Shikibu’s thousand-year-old novel. He was the thirty-eighth generation of his family to serve as priest of this shrine, which was established in 794, the year Kyoto became capital of Japan. The shrine commemorated the spirit of Emperor Kanmu’s brother, Prince Sawara, among other spirits, who themselves needed placating lest they did more harm than good. Located to the north of the imperial palace, it was originally established to protect the imperial line. From my living room window, we could see the grove of trees where the shrine was located. I suspect it hadn’t always been there. In Kanmu’s time the palace was located further to the west. But the shrine was certainly in its present location by the fifteenth century, because it became the tinderbox for the Ōnin War, which went on to destroy most of the capital.

The altar was erected along the west wall of my dining room to face the east, and tall trays in unvarnished wood were laid on it for the offerings of salt, rice, sake, and water. Fujita had brought as gifts a tin of cookies and some kind of jelly made with mandarin oranges, and these were set out on the altar. Seeing that I had some mandarin oranges and a bunch of bananas, the priest asked if these too could be put out as offerings to the gods. I would get to eat them after, he said. I was happy to oblige. Fujita and I sat on chairs facing the altar.

The priest began by announcing that the purpose of the ritual was to cleanse the space of any harmful spirits. He asked us to stand and to follow suit as he bowed, clapped his hands twice and bowed again. He asked us to be seated. Then he announced my address and the shrine’s address and invoked the gods of the land on which the condominium stood, as well as the gods who protected the shrine. He asked us again to stand and bow. He summoned the gods to come into our presence. Fujita became a little unsteady on his feet, at one point dropping into the chair, then bouncing up again, as if he were a Pentecostalist filled with the holy spirit. Then, in the presence of the gods, the priest prayed for the peace of any unrestful spirits, shaking a wand to which were attached paper streamers. He turned toward me and Mr. Fujita and asked us to follow him as he laid a branch of sacred sakaki on the altar. He then asked me to join him as he blessed the cardinal points of the compass, moving clockwise from the northeast to southwest, west, northwest, and north, shaking his wand and casting handfuls everywhere of rice and little paper squares like confetti. He would shake his wand, then pass it to me and reach into a box for the confetti and a bowl for the rice and scatter it throughout the apartment, first in the bedroom facing Mt. Hiei to the northeast, then the living room, then in the entranceway at the southwestern end of my apartment, returning to the kitchen and master bedroom. He then asked me to take some white sand he had prepared from a box, along with salt, confetti, sake and water, and sprinkle them all outside the apartment, on my balcony, outside my front door, and later (discretely) at the four corners of the building downstairs.

The whole ritual took about an hour. Fujita explained that arranging exorcisms was a common task for a real estate agent, and typically he employed the priest from this shrine. Sometimes customers ask for it as a matter of course. Whether a place is thought to be haunted or not, it’s considered good insurance to have a priest bless a place, whether it’s brand new or had been previously occupied. A compelling argument could be made in the case of the latter, because former occupants leave traces of their energies, whatever good or bad fortune they might have had, and it was important to clear the space so a new occupant could start afresh. Fujita hastened to add that the priest himself wasn’t clairvoyant. Another friend of his was, however, and occasionally he called on him to do an exorcism. A case in point was a suicide of a friend of his, who had wandered up into the hills behind the Kamigamo Shrine further north, and hanged himself there from a tree. They held a ceremony on the very spot to placate his spirit. The forest there is known as a place where people go to die. One could hike there during the day, but you wouldn’t want to be caught there at nightfall.

The priest added that the ritual he’d just performed wouldn’t necessarily get rid of any spirit that may have lingered after my erstwhile neighbour’s suicide. The point wasn’t to drive them away, but rather to make the living at home with them, and reconcile the spirits to their new occupants. Were a ghost to appear it would be wrong to react with terror, both for the sake of the spirit as well as the living. Cultivating a generally healthy attitude to the supernatural was best, even if one didn’t generally sense unseen presences. It would be enough that the air was cleared, as it were. One could go on living there comfortably, without undo worry over what might have happened next door, sometime in the past. Indeed, the air felt fresher, or was it just my imagination? Fujita seemed the most relieved of the three of us.

Later, I told this story to a Japanese friend of mine, who said on no account would he ever live in such a place, because he would never get out of his head that, steps away, someone had taken their own life. Every day he looked out the window over the city, every time he looked over the balcony at the street below, he would be reminded of that. And to be reminded would be to fall under the influence of that misfortune.

They dismantled the altar. The cookies, mandarin oranges, and bananas, now blessed, were returned to me, as were the sake and salt. And I had a little box of white sand to sprinkle in places to purify everything.

At my entranceway is an old millstone that had come from my mother-in-law’s place in Nishiki Market. Years ago, she had fallen ill. When she could no longer look after herself, she and her things moved into our house in Katsura. All but the millstone. That night, my wife said, the millstone came to her in a dream, asking “why did you leave me behind like that?” The following day she retrieved it and put in in the vestibule between the coffeeshop and our private quarters behind. When my wife died and I moved my things out of the Katsura house to my new apartment, I consulted the kids about the millstone. None of them claimed it, so I took it with me. It guards over the ura-kimon. While the northeast was considered the unluckiest direction, the portal for devils to enter your home, as we all know, the devil is just as inclined to enter by the back door, from the southwest instead.

After the exorcism, I made sure to sprinkle a little pile of salt on top of the millstone. I heard the concierge outside with an assistant, busily sweeping the salt and sand off the landing outside my door. I myself was leaving for work and when I got to the elevator, the two were about to descend. They didn’t stop to let me on, so I had to wait for the elevator to reach the ground and come back up again. I would have made for awkward company in any case.

When I got home from work, I got to sweeping up my apartment, which was scattered with confetti and grains of rice. It was more like the aftermath of a wedding than a funeral.

I’ve had my exorcism, but I am still waiting for the new bidet.

* * *

To learn more about Cody Poulton, click here. To read more of his writings on the WiK website, please see the following links:

Uncle Goldfish

Poulton, In Transit

Bury My Bones in Toribeyama

Under Kiyomizu

WiK Competition 2017 Runner-up (Poulton)

Recent Comments