To be confirmed

To be confirmed

To be confirmed

On January 21, nine people gathered to hear Timon Screech’s talk, which was abundantly illustrated with interesting photographs. This talk was organized by WiK with the locale assistance of Paul Carty.

Timon Screech has about 20 books to his credit, including Tokyo before Tokyo and The Shogun’s Silver Telescope. His speaking style reflects his enthusiasm, especially for interesting sidelights on history which illuminate international trade, diplomatic connections, and political machinations. This talk was a good example of this.

It had been a while since I thought about Japanese history, and it is heartening to realize that people like Timon Screech make it their life’s work, as it is so fascinating in so many ways. The title made me wonder what, in this context, is meant by “avatar”, which is defined as an embodiment or symbol, in human form, of a concept, philosophy, or deity. It had not occurred to me to think of Tokugawa Ieyasu in this context, so it filled in some blanks for me with regard to one of the most important characters in Japanese history.

It seems impossible to talk about Ieyasu, the Great Unifier of Japan, without talking about his predecessor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The beautiful and ornate mausoleum of Ieyasu in Nikko, in the north of the Kanto Plain, echoes that of Hideyoshi at Amidagamine in the foothills of Kyoto.

Many historical figures sought “deification” as avatars of Shinto kami 神, or Buddhist figures. They also sought connection with the Imperial Family in order to confer legitimacy on their government, especially those in the new “eastern” capital, Edo, home of the shogunate, which was considered barbaric compared to the “western” court of Kyoto, where the Emperor resided. Both Hideyoshi and Ieyasu desired this kind of connection.

It is important to remember that at this period of history, Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines were not differentiated as they were later. For example, personalities like Sugawara no Michizane became the avatar of Monju Bosatsu (a Buddhist saint and patron of education) and was also, as a kami, associated with Kitano Tenmangu Shrine in Kyoto.

In any case, the warriors who began the shogunate knew that they were looked down on by the Kyoto court, and by associating themselves with dieties and other important figures sought to give an air of legitimacy to their Eastern area. Thus, Ieyasu was made a daimyojin, the highest level of kami, and also became an avatar of the Buddhist deity Yakushi Nyorai; the person engineering this was a Tendai (Mt. Hiei in Kyoto) monk called Tenkai, who was charged with rehabilitating the ancient historical site of Nikko. In the process he started the cult of Ieyasu at that place. This mausoleum is referred to as Toshogu, “the shrine of Tosho”. Tosho was the posthumous name given to Ieyasu, and gu is an Imperial shrine. Nikko means “light of the sun”, (a word describing the Emperor), and the fact that this site was in the East, which is associated with the sun, bound these close together. Specifically, Tokugawa Ieyasu was seen as a light (lantern) which assisted the sun of the Emperor, and the lantern became a symbol of this; many different and interesting lanterns are scattered around the Nikko mausoleum. Lanterns are also used in the worship of Yakushi Nyorai.

For example, a metal lantern, which is a copy of the one at Daitokuji in Nara was donated by Ieyasu’s granddaughter, Masako, who was married to Cloistered Emperor Go-Mizuno-O. Others included two metal lanterns donated by Date Masamune, a famous general of both Hideyoshi and Ieyasu, and three of Dutch manufacture, which were purported to be gifts from Holland, Okinawa and Korea through various political and diplomatic machinations.

There is a very complex hierarchy of lanterns, both those who donated them and those before whom they were burned. The material of metal was the highest level of this hierarchy.

Timon Screech said he is presently working on a book on the topic of this talk. We await the appearance of this book, which will certainly shed light for readers of English on this interesting and important part of Japanese history. Our thanks to him for speaking to us.

* * *

Information about Timon’s academic background can be found within the original event listing at this link.

In the foothills of Mt. Hiei, in north-east Kyoto, is a Japanese cultural centre dedicated to the dance. Designed by the same architect who planned the State Guest House, it is a sprawling complex of rooms, magnificent gardens, stages, and halls. When money is little object, this is the result.

The first room into which I was shown was a large reception room with Regency-style sofas and chairs. The window, which stretched completely along one wall, looked out onto a raised garden of pink azaleas, into which large rocks had been set, with small paths leading up behind them. It was rather like looking into a silent aquarium.

Another long wall was made completely of black lacquer, with intricate and wonderfully conceived mother-of-pearl inlay. Though considerably simpler, the conception reminded me of the Amber Room in the Catherine Palace near St. Petersburg. A large sea-shell on a small table nearby bore similar patterns on the inside.

On the second floor was a large hall with a stage and all the accompanying paraphernalia of lights and curtains. There was a large pine tree painted on the back board for the Noh theatre. Gods are said to descend into the human world from it.

Continue readingWhen I moved back to Kyoto in August I had to find somewhere to live for the long term. The old house in Katsura was no longer liveable; besides, I wanted to be closer to town. A friend of a friend, Mr. Fujita, was a real estate agent, so I asked him if he could find me a few places to look at. I told him my price range and roughly where I wanted to live. In a couple of days, he had three places lined up, so we met the next Saturday to see them. The first was an apartment in a condominium building, the second a machiya, or traditional townhouse, and the third was a three-bedroom house built sometime in the ’eighties not far from the river.

It was a blazingly hot day just before Obon, the festival when the spirits return from the dead to be entertained by their offspring. After three days, the spirits are sent home with bonfires on five of the surrounding mountains. If you can stand the heat, it’s one of the most beautiful of Kyoto’s annual festivals. Many try to find the roof of a taller building to witness the lighting of the okuribi, or “sending fires.”

We first visited the condominium apartment, which was located on the top floor of a high rise in the north of town. Though an older building, I was assured that it had been built after strict laws had been enforced to make tall structures like that safe in all but the most devastating of earthquakes. The apartment had been completely renovated, with new flooring and wallpaper and a new kitchen with an induction range. The only thing unchanged apparently was the toilet, from which issued a mouldy smell, which bothered me. Mould had been one of the things that had driven me out of our old house in Katsura.

The best part of the place, however, was the extraordinary view to the west, north, and east of the city. From the bedroom windows I could see four of the five mountains where they light the bonfires of Obon. To the west was Mt. Funaoka and Hidari Daimonji, and behind that Atago, Kyoto’s highest mountain; to the north, Takagamine and Kurama; to the northeast, Mt. Hiei; and east, Nyoigatake, otherwise known as Daimonjiyama. These mountains to the east and west are called Daimonji because the character for “big” (大) is traced out on their slopes. The outlines of a sail ship and the characters 妙法 (myōhō), meaning “wondrous dharma,” were inscribed on the sides of two other mountains to the north. A fifth mountain with the image of a torii gate was hidden behind a hill over to the northwest in Arashiyama. You could see it only if you lived over that way.

I thought to myself, what a great place to throw a party when they light up the mountains at Obon! But better yet was the effect when I opened all the windows. A refreshing breeze blew through, from west to east. One hardly needed the air conditioning. For most anyone in this city, which sits in a basin hemmed in by mountains, the summer is oppressively hot and humid and one can scarce survive it without the blast of an air conditioner.

The second place we saw was the machiya, which was located further to the north behind Imamiya Shrine. The place had been modernized with a new kitchen and bathroom, but it was hot upstairs and it was hemmed in by other houses. I imagined the downstairs would be dark and cold in the winter. The third place was a fine house, well built, but much too large for a single person like myself.

I could have asked the realtor to show me more places, but classes were beginning soon, I was sick of moving from one Air BNB to the next, and I was taken with the first place I’d seen. I am not one for making snap decisions, especially on first impressions, but I liked what I saw and knew I couldn’t find anything like it anyplace else. After a couple of weeks of negotiations and pieces of paper passing back and forth, the contract was sealed and I had the keys.

Continue readingMembers and Followers of Writers in Kyoto are cordially invited to join Timon Screech for a presentation on the topic New Light on Nikkō: The Cult of Tokugawa Ieyasu as Great Avatar.

<Event Date>

January 21st, 2023 (Saturday)

<Time>

16:30 ~ 18:00 (Doors open at 16:15)

<Venue>

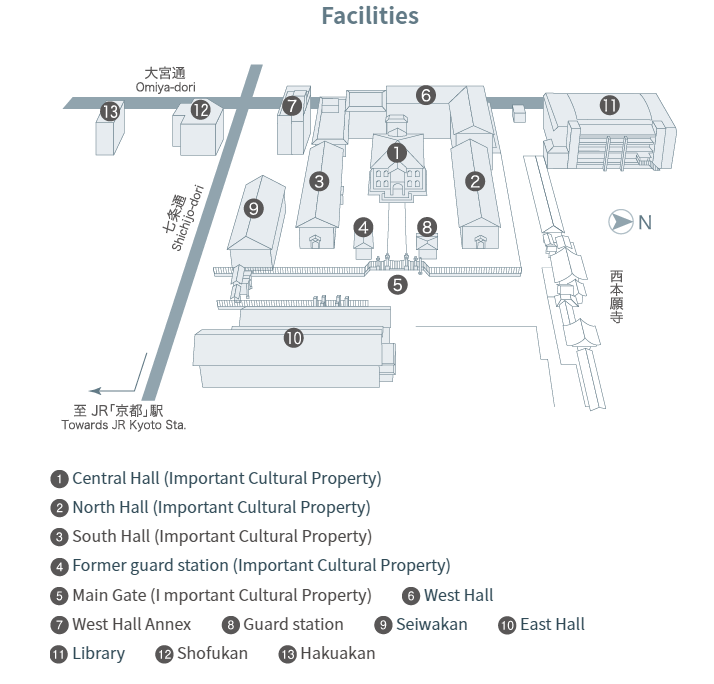

Ryukoku University Omiya Campus, East Hall, Room 208 (approx. 10 minutes on foot from Kyoto Station’s Central Entrance and next to Nishi Hongwanji Temple) [Google Maps ; Building #10 in the image below]

<Participation Fee>

Free for paid members of Writers in Kyoto. For other participants, a one-coin donation of 500 JPY at the door would be appreciated.

*Please RSVP if possible by clicking on this link and entering the names of people who plan to attend.

—————————————

Courtesy of Wikipedia….

Timon Screech FBA (born 28 September 1961 in Birmingham) was professor of the history of art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London from 1991 – 2021, when he left the UK in protest over Brexit. He is now a professor at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies (Nichibunken) in Kyoto. Screech is a specialist in the art and culture of early modern Japan.

In 1985, Screech received a BA in Oriental Studies (Japanese) at the University of Oxford. In 1991, he completed his PhD in art history at Harvard University. As well as his permanent posts, he has been visiting professor at the University of Chicago, Heidelberg University, and Tokyo University of Foreign Studies and guest researcher at Gakushuin University and Waseda University in Japan, and at Yale, Berkeley and UCLA in the USA. His main current research project is related to the deification of the first Tokugawa shogun, Ieyasu, in 1616-17, and his cult as the Great Avatar.

In July 2018 Screech was elected a Fellow of the British Academy (FBA).[1] Screech’s work had been translated into Chinese (Taiwan and PRC), French, German, Japanese, Korean, Polish and Romanian. His leisure interests are aleurophilia, learning Burmese, and cultivating the former Kingdom of the Ryukyus.

Book Review of The Way of the Fearless Writer by Beth Kempton (Piatkus 2022))

Reviewer: Rebecca Otowa

(Beth Kempton is a writer and mentor who spent a year in Kyoto in the nineties, and has travelled back and forth frequently since then. Her books may be found on amazon.com.)

Now that the New Year’s season has passed and we are safely into 2023, many of us might be thinking, “How can I make my next year of life meaningful?” Here’s a book for you to find meaning in your own writing life.

The few moments of time for creativity that we carve out from the rest of our lives; the moments when we really feel we have something to express that has never been said in quite that way before; we wish to have them, and have more of them – no matter what our previous experience of writing has been. And we all think of ourselves as writers, else we would not be in this group.

As Beth says (p. 70) “… being a writer has nothing to do with other people’s validation, having things published, or being paid to write… Being a writer is writing. Being a writer is capturing things that spill from your head and heart, and putting them on paper. Being a writer is expressing the human condition and experience of existence in words.”

To this end, we can use this book as a guide to finding or re-finding our writing voice. Sprinkled liberally with anecdotes from her own experiences, Beth, who already has a flourishing online mentoring business called Do What You Love , and four other books published (including Wabi Sabi), here gives us guidelines for feeling our way (back) into the joy of writing.

The book presents writing as a practice for self-awareness, staying in the present, even enlightenment, and is based on three Gates of Liberation of Buddhist practice, called Mugenmon (The Gate of Desirelessness), Musoumon (The Gate of Formlessness) and Kuumon (The Gate of Emptiness). For each Gate section, there are four chapters, plus a Journey Note and a Ceremony when the Gate is safely passed. Tucked into each chapter are writing prompts in boxes, called “Write Now”. Other suggestions for writing are also provided, based on the theme of the chapter.

So, that covers the writing. Where does the “fearlessness” come in? I would say, both as a writer and as a Buddhist practitioner, that the book doesn’t pull any punches when it says that when you write, you may find yourself opening and mining memories of forgotten times, places and people and how they made you feel. It takes fearlessness to keep going when this happens, but the rewards are great. Because writing is, according to Beth, “about ritual, dedication and commitment, developing an acute awareness of beauty, dancing with inspiration, listening to the world outside yourself and going deep within.” (p. 7)

Sound like a tall order? It may seem daunting. But please allow me to add something of my own to this. Recently I had a long talk with a 26-year-old Assistant Language Teacher in my town (from Jamaica!), and she said that one of her perennial problems was that she lacked discipline. After many years of struggling in this department myself, I have come to the conclusion that within our character, either there is a bent toward self-discipline, or there isn’t. I know, after many trials, that to say to myself, “From now on, I’m going to do A every day” is a recipe for disaster. If you are a self-punishing type, it can be excruciating when, as inevitably happens, you fall from that lofty peak.

But I am not without self-discipline. I usually finish what I start, eventually. It’s just that I have found that, for me, making lists and telling myself, “if I don’t do this, I’m a terrible person” just doesn’t work. The Buddhist practice I am now doing says that everything, success, failure, whatever, is part of the path. And the path is something we will be walking all our lives, perhaps many lifetimes. So what’s the rush? What I told the ALT was this: Pick just one activity that you consider a high priority, whether it is eating breakfast, some cleaning chore, anything, and try to do it for a month. Don’t beat yourself up if you don’t do it every day. Just keep track of the number of days you did do it. At the end of the month, if you are satisfied with the total number of times you managed to do it, add another activity. If not, do another month concentrating on the first activity. And perhaps it would be good to consider WHY, sometimes, you were unable to do it. Maybe there was just no time that day, or your routine was disrupted. Maybe you just didn’t feel like it. And that’s OK. I did this in December with stretching exercises and walking. When I totaled them up, I found that I had only done these things 2/3 of the days of December. Well, that’s a lot better than 0. Maybe January will be better.

But some people thrive on this kind of discipline. No less a writer than Stephen King suggested that aspiring writers “write something every day”. A ritual can help, as Beth suggests. Treating writing time as a really important thing, not relegating it to minutes of tired time just before bed, etc., can help too. I think personally that it is important to know yourself when you attempt this kind of discipline. I think that just jumping in and writing can help with this self-awareness too. That’s really what Beth’s book is about. Self-awareness often requires fearlessness.

If you feel that now, in the New Year, is the time to pick up the reins (or the pen, or the keyboard) and write, this book provides an easy-to-read, friendly guide to doing that.

It was one of those sparkling summer days when the pale blue sky seems to stretch higher than usual. I was running errands near home and took the path along the river to avoid traffic and enjoy the view. I looked back and forth to the river as I cycled along, spotting some of the usual inhabitants – the eponymous ducks, herons and little egrets – and then, an unexpected one. I stopped my bike to gawk at it. At the edge of the grassy bank in the middle of the river was one of those things that there’s a sign about down at Demachiyanagi. A “neutrino,” or something, because that’s not the right word – but something like that. And if I’ve ever seen a South American beaver-like rodent smile, that’s what it was doing now. The audacity! And then, just like that, in the brilliant sunshine of a Kyoto summer, it took a moment to give its butt a good, long scratch.

Continue reading

The November sun Dazzles our faces with eyes closed The bright glow of coloured leaves Is not of this world Here, today It is another universe That looks like the world As it is Of islands, rivers, mountains, oceans A monochrome universe Emerges from the stone Expanding my mind Falling on the moss Like shooting stars The maple leaves Swept by the autumn wind Or by the gardener In the twilight From the path of Yoshida Hill I walk along the candlelight on the ground A black butterfly As big as my hand Escapes from the darkness of the undergrowth - Or is it a bat? A tiny tea house Above the bamboo grove of Kodai-ji temple Under the full autumn moon That illuminates the scarlet maples And the cold of a night Full of promise Drop after drop The basin of water fills With the inebriation of life Under the amazed gaze Of a wise man silent Like the passing of time Small granite monk's heads In a sea of green moss Smile at life As well as to death Autumn rings hollow Under the crackling sound Of leaves tinged With the past I watch my thoughts Reflected in the clear water Of the lotus pool Then floating Like a sea of clouds In a distant sky.

Under the clouds diving into water The absence of a new beginning In the middle of this inland sea Calm as a shoreless lake I consider the possibility of an island Swaying in the wind - A solitary jellyfish!

The number eight bus abandons me at the curve Stone stairs going down Stone stairs going up The face of the Buddha is invisible In this mountain temple The Japanese maples smile Behind their faces scorched by the sun And the coolness of the mountain nights Stairs again and again The sound of a Japanese lute Makes the humid air vibrate on the river I follow the path that follows the water Climbing over blunt rocks And suddenly the sight of a vermilion bridge Amidst the vermilion maples A man is fishing with a line Sitting on the granite pebbles As in an old print by master Hiroshige - The hanging bridge of dreams.

*************************

These poems have been translated from French by the author. The book Rêves d’un mangeur de kakis is available from the publisher (www.michikusapublishing.com) or directly from the author.

For other writing by Robert Weis, see Mind Games in Arashiyama, or 71 Lessons on Eternity. For more on his travels, see his account of a walk from Ohara to Kurama here, or his spiritual journey to Kyoto here. His account of Nicolas Bouvier in Kyoto in the mid-1950s can be read here.

The relationship between David Bowie and Kyoto is a source of endless fascination. Less well known is the connection between the city and the mega rock band Queen. Like Bowie, who I wrote about in April, Freddie Mercury was particularly attracted to Kyoto.

Queen has several links with Japan. For example, more than 1,000 fans flocked to Haneda Airport to glimpse the quartet during the 1975 Sheer Heart Attack Tour, their first tour of Japan. In addition, Japanese lyrics account for a part of “Teo Torriatte (Let Us Cling Together),” a closing track on the 1976 album ‘A Day at the Races’.

Continue readingThe dharma of natural laws Initiate a sublime conclusion: “No cause, no cause.”* Zen sermons for all their flaws Frame an eloquent elocution The dharma of natural laws To escape ideological claws One source of absolution: “No cause, no cause.” Dreams must give us pause† The crystal clarity of illusion The dharma of natural laws Being beyond is will or was Exalt religious revolution: “No cause, no cause.” No curse no applause Only a salient solution: The dharma of natural laws: “No cause, no cause.” *cf. King Lear (4.7.75). †cf. Hamlet (3.1.68).

******************************************

Preston Keido Hauser is a longtime member of Writers in Kyoto, a poet and a player and teacher of the Japanese wind instrument shakuhachi. He has been in Kyoto since 1981. His website may be found at www.keidokyoto.wordpress.com. To read more of his work on the WIK website, click here.

© 2025 Writers In Kyoto

Based on a theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

Recent Comments