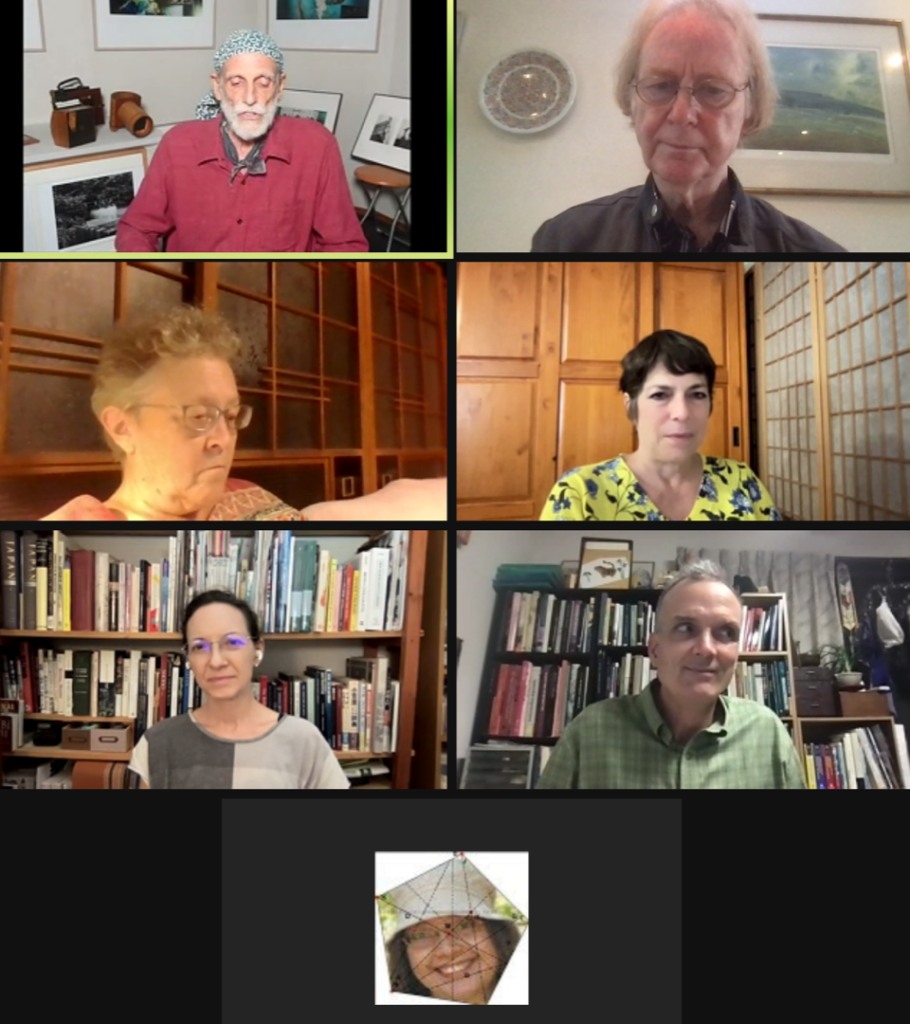

An Edited Funeral Service Talk in Osaka, Japan, 2022-04-29

by Reggie Pawle

(For reasons of confidentiality, the name of the deceased has been changed.)

Master of Ceremony: As other people have said, exactly one year before Richard received his diagnosis, he lost his beloved wife (through a very unexpected tragedy). They were married for over twenty years and over the next couple of years he worked, he saw people, he went places, and he did what he had to do, but the loss never faded and the pain was always there. A few months ago Richard invited Dr. Reggie Pawle to talk to us today about grief and loss and healing.

Reggie: Richard asked me to speak about grief and how to deal with grief. A lot of what I wanted to say has already been said, because people here seem to know about grief. I’ll try to add some understanding to what has already been said.

I was Richard’s counselor for about 11 years. I know him in a different way than most people here know him, because he only came when he had a deep challenge and I only saw him in my office. Still, even though we always talked about problems, the light, the brightness of Richard that has been talked about and shown here today, was really clear all the time in the midst of all his struggles.

When you lose somebody through death, the initial reaction is always shock, no matter how much you’ve been prepared, how much you know about it. The finality of death, right, you’re never going to be able to meet the person again. It seems unreal, the surreality, the disorienting feelings that come up, the mystery, all of the unknowns, the intensity. You don’t know what to do. In daily life we don’t commonly have these kinds of deep and strong feelings. The pain, the hurt, the confusion.

The deeper you love, the deeper you grieve. Your grief and your pain is part of your connection to your loved one. As time passes, grief and pain become one of your most tangible connections that you feel for your loved one. You might not want to let these painful feelings go. You might feel guilty if and when the pain lessens over time, as if the lessening of pain is because you are caring less for your loved one. Regrets about “if only I had…” can plague you. Loneliness can be strongly felt. You cannot share together with your loved one anymore. You do not get the feedback and responses that were so much a part of your relationship together. All of your future plans cannot happen. You can’t accept that your loved one has passed away. The feelings of loss, the feelings of emptiness. How can you go on?

I am going to read a couple of poems by Earl Grollman (1995), who wrote a book (Living When a Loved One Has Died) about grief. This poem is entitled, ‘And It Hurts’:

When you lose, you grieve.

It is hard to have the links

with your past severed completely.

Never again will you hear

your loved one’s laughter.

You must give up the plans

you had made; abandon your

hopes.

Like all people who suffer

the loss of someone they loved,

You are going through a

grieving process.

The time to grieve is NOW.

Do not suppress or ignore your

mourning reactions.

If you do, your feelings will

be like smoldering embers,

which may later ignite and

cause a more dangerous explosion.

Grief is unbearable heartache,

sorrow, loneliness.

Because you loved, grief walks

by your side.

Grief is one of the most basic

of human emotions.

Grief is very, very normal.

***********************

Grief is a normal emotion. It’s important to understand that each person grieves differently. You are your own expert in how to grieve. With grief you can’t say how to do it, because everybody does it in their own way. There’s no timeline for grief. It comes in many forms, like, for example, for those of us who are gaijins (foreigners) in Japan, the experience of a long plane ride back to our home country when a family member has died. In my own case when my mother died, I booked a return ticket for two days later and canceled all my appointments, except for one. This woman begged me, so I said yes. Then she came the next day and told me her story of just returning to Japan from being in her home country to be at her mother’s funeral. She cried. I didn’t tell her my own story, but I cried, and we cried together. It was surreal. Then the next day I left for my own mother’s funeral. There’s no explaining death.

This is a diversity approach to life and death. Everybody has different experiences and everyone responds differently. It is important not to let social ideas of how to grieve tell you how you should grieve. Live your grief process.

This is a second poem by Earl Grollman (1995), called, ‘But It Hurts… Differently’:

There is no way to predict

how you will feel.

The reactions of grief are

not like recipes,

with given ingredients,

and certain results.

Each person mourns in a

different way.

You may cry hysterically,

or

you may remain outwardly controlled,

showing little emotion.

You may lash out in anger against

your family and friends,

or

you may express your gratitude

for their concern and dedication.

You may be calm one moment –

in turmoil the next.

Reactions are varied and

contradictory.

Grief is universal.

At the same time it

is extremely personal.

Heal in your own way.

****************

Talking to other people at this time is sometimes awkward. They can be very irritating. Platitudes don’t work. Sometimes people just don’t know what to say. Sometimes you will hear dimwitted questions like, “How do you feel?”, when a better question would be, “How will you remember them?” Everyone it seems has an immortalized memory in their heart of their loved one.

You still have to deal with the business of living. If you park in a bus stop, like I did when I was upset after being informed that my grandfather had died, the local laws will still apply to you. It was the middle of the workday and I had to go to a building for a work function. I couldn’t find a convenient parking space. I recall myself thinking, “I can’t deal with this. I’m barely holding it together. I’ll park in the bus stop.” So I went in for a few minutes, only a few minutes, came back out, and I had a parking ticket.

Just manage each moment, hour, that leads to another day without your bright and lightness that shone so vibrantly before. Try to relinquish your sense of control and agenda and ride it out, while being attentive to what’s going on, to what you are experiencing. Do what helps you. Some share with others who have had the same loss and find incredible support and strength. Listening to others’ stories can help, as does telling your stories, like we’re doing here today. Crying is natural when you are grieving. Some write haiku (17 syllable poems), some read books like Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, some go for walks in the forest.

As some have been doing here today, it is ok to give yourself license to express positive emotion and affirm other aspects of yourself that you value outside the tragedy. It can be psychologically healthy to focus on the parts of your identity that are not touched by the tragedy. It is ok for the grieving athlete to play in an important game. The same goes for the student who wants to take their final in the wake of a campus tragedy. Some have said that doing so will makes them feel more in control and helps them cope better down the line. There is not a right way or one way to grieve. Find your personal way.

You’re dealing very directly with the existential realities of death and time. Everyone dies and nobody can stop time from continuing and passing. Grief can feel like collapsing on the ground. Yet it is through being on the ground that you can stand up again. Japanese people invoke this understanding when they say about Daruma (the person who brought Zen Buddhism to China from India), “Seven times falling, eight times standing”. The number is one more for standing than falling because the assumption is it is natural for a person to stand up and be active in life. However, many times we get knocked over. The belief is that each time something in life knocks us over, we need to find our ground and stand up again.

Death happens to everyone. Therefore, it can’t be bad. Your loved one is okay and you also will be okay when you die. It is written (Inoue, 2020) that the wife, Yoshie Inoue, of Zen master Gien Inoue said to her husband on June 2, 1946, “I’m indebted to you for all that you’ve done for me these many years. Now, I’m going to die.” Gien said, “Are you alright?” Yoshie laughed, saying, “I’m alright,” whereupon she died. You don’t have to be afraid of death, you can find your way to deal with the passing of your loved one from this world, and you don’t have to be alone. You can be at peace.

So, (as I turn to face the large photo of the deceased on the altar) I want to say, thank you Richard, for what you’ve given to all of us, and for me personally, for the brightness that you always had in the midst of all your intense struggles that we shared together. You live on as a part of us.

*********************

References:

Grollman, Earl. (1995). Living When a Loved One Has Died. Boston, MA, USA: Beacon Press, pp. 13-16.

Inoue, Gien. (2020). (Trans. D. Rumme and K. Ohmae). A Blueprint of Enlightenment. Olympia, WA, USA: Temple Ground Press, p. 31.

*********************

For more about Reggie Pawle and his psychotherapy work, see www.reggiepawle.net. For his self-introduction, see here. For his work combining psychotherapy and Zen, click here. For his piece on Zen and the Corona crisis, see here.

Recent Comments