by Jann Williams, April 21, 2022

It was not until my mid-50s that a deep interest in Japanese culture was stirred, seeking lessons on how to connect people and nature in a quest for sustainability. The elements of nature are my guide, embedded as they are in all aspects of Japanese life – whether it be through interactions with the physical environment, the ubiquitous presence of inyo gogyo (yin-yang and the five phases of earth, water, fire metal and wood), or the ‘great’ Buddhist elements of earth, water, fire, wind, space and consciousness.

To read Japanese at the level required for my explorations would take several years of concerted practice I’ve been told – especially for the specialist texts I’m interested in. Not having the luxury of time, I have relied on bilingual books and written translations of Japanese works in addition to my extensive library of English books and articles on Japanese culture. Right from the beginning I would like to thank all of the translators I know, and those I don’t, for making works in Japanese available to those of us who are unable to read the primary source. Here I relate my encounters with translation over the six years since my intensified quest to explore the elements in Japan began, and the crucial role that Writers in Kyoto has played.

Until recently most of the translations on my bookshelves have been either non-fiction like Kukai – Major Works (translated by Yoshito S. Hakeda) or Japanese classics such as Essays in Idleness (my copies independently translated by Donald Keene and Margaret McKinney) and The Tale of Genji. All but one chapter of the latter book was translated into English by Arthur Waley between 1925-1933. There have been many other versions, including one in 2018 subtitled ‘the authentic first translation of the world’s earliest novel’ translated by Kencho Suematsu. Each translator brings their own experience, personality and interpretation to their art, with some translations favoured over others. Hence for some titles, such as Essays in Idleness and the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters) I have at least two copies to compare and contrast the different interpretations. This includes the first English translation of the Kojiki by Basil Hall Chamberlain, published in 1882 when there was growing interest in ‘things Japanese’ in the West. Indeed Chamberlain published a book with that very title (Things Japanese) in 1891.

The Japanese work that I have the most translations of is Hojoki (The Ten Foot Square Hut), the classic recluse story written by Kamo no Chomei in Kyoto in 1212 AD. It is a tale of withdrawal from and reflection on a world fractured by earthquake, windstorms, fire, plague and war. Natsume Soseki undertook the first English translation in 1891. My earliest translation is from 1928 (by A.L. Sadler), complemented by the 1967 translation by Donald Keene, the beautifully illustrated 1996 translation by Yasubiko Moriguchi and David Jenkins, a 2014 version by Meredith McKinney, and most recently the 2020 and 2022 bilingual translations by Matthew Stavros. The strongly elemental nature of Chomei’s prose captured my attention:

“Of the four elements,

Water, fire and wind cause damage most frequently.

The earth only sometimes brings disaster.”

This translation is from In Praise of Solitude published by Matthew Stavros this year. The four elements Chomei refers to are Buddhist in origin. They are related to the impermanence of life, a Buddhist concept that permeates Hojoki. Matthew spoke about translating Hojoki in a Writers in Kyoto (WiK) Zoom session in November 2020 which provided a broader context for the translation.

Matthew’s presentation was one of many opportunities WiK has provided to expand my connections to, and appreciation of, the world of translation. Juliet Winters Carpenter, an award-winning translator of modern Japanese literature, wrote the Foreword of the third WiK Anthology that Josh Yates and I co-edited. Our first meeting in person was at the Kyoto launch of the Anthology in June 2019, not long before Juliet moved back to the United States. Her encouragement of my quest, even though I couldn’t read (or fluently speak) Japanese, was heart-warming. Several members of WiK are also translators. Recently, WiK member Yuki Yamauchi translated Rona Conti’s essay ‘What does this say, sensei’ from the 4th WiK Anthology to gift to her calligraphy teacher in Japan. This is one of many examples of the support and encouragement within this writer’s community, which centres on our shared connections with Kyoto.

During the COVID pandemic, Writers in Kyoto have held a diverse series of Zoom sessions, including by Matthew Stavros. These have been a life-saver for those of us unable to travel to Japan for an extended period, now 2.5 years and counting. In June 2021 Ginny Tapley Takemori, a freelance translator of early modern and contemporary Japanese novels and short stories, was one of the speakers. Her insights about the translation process were illuminating. Ginny shared some of the joys and challenges of translating from Japanese to English. She spoke about helping set up a collective called ‘Strong Women, Soft Power’ to promote the translation of more women authors. Activism in the translation community had never crossed my mind. It was interesting to hear, among many other comments, that not all authors see the translation before it is published. Ginny’s talk helped me see translation in a completely different light.

Following Ginny’s presentation my library of translated works by contemporary Japanese authors has expanded considerably. This included buying two books that Ginny translated – the world-wide sensation Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata and the enchanting Things Remembered and Things Forgotten by Kyoto Nakajima. Translations by Polly Barton (Where the Wild Ladies Are by Matsuo Aoko), Juliet Winters Carpenter (The Easy Life in Kamusari by Shion Miura) and more now grace my library shelves. Interviews with several translators on Books on Asia, a podcast hosted by Amy Chavez (another WiK member), also influenced my selection of books. Both the stories and interviews have opened up fascinating and pertinent worlds.

Janine Beichman’s translation of Well-versed: Exploring Modern Japanese Haiku by Ozawa Minoru is one I return to often. Poetry is an essential part of Japanese culture and includes many references to nature’s elements, especially the seasons. Modern haiku builds on a poetry tradition of over 1200 years. While I had many translations of poetry beginning with the 9th century Man’yoshu anthology, and several books about Basho’s haiku, Ozawa Minoru’s contribution was my first exposure to a range of contemporary Japanese poets. The text accompanying each poem provides further insights.

The commentary provided by translators is also valuable. Roger Pulver’s recent book The Boy of the Winds, where several stories by Miyazawa Kenji are translated, includes some thought-provoking comments about the nature of nature in Japan. In October 2021 Roger spoke about the nuts and bolts of translation in a wide-ranging webinar. In it he covered the rhythm and logic of the Japanese language compared to English, the importance of translators taking a stance and putting their own stamp on a translation, and much more. Strangely, I hadn’t realised how much influence translators can have; capturing the same feeling as the original Japanese is what Roger strives for. His comments made me better appreciate the nuances, decisions and emotions that can be involved in translating Japanese into English. ‘Each translation will be different’ is a message that came clearly through.

Keeping this in mind, translations of other books on my shelves related to the natural world include Flowers, Birds, Wind and Moon: The Phenomenology of Nature in Japanese Culture by Matsuoka Seigow (translated by David Noble) and A Japanese View of Nature: The World of Living Things by Kinji Imanishi (translated by Pamela J. Asquith, Heita Kawakatsu, Shutsuke Yagi and Hiroyuki Takasaki). (What it would be like working with a number of translators I wonder?) These works happily sit aside the academic translations in my library. One I’m particularly thankful for is the translation by Hendrik Van der Veere of Gorin kuji myo himitsushaku (Secret Explication of the Mantras of the Five Wheels and the Nine Syllables), written by the 12th century Shingon monk Kakuban.

It would be interesting to speak to some academic translators of Japanese works, especially historical and non-fiction literature. Would their process differ from those who translate contemporary fiction? How many ‘feelings’ would come into play? From my involvement with the Pre-Modern Japanese online forum, I have followed long debates about the translation of individual words and concepts. The Japanese language has evolved through several stages/forms, making translation of the older texts a particularly challenging pursuit.

Many kanji outside of day-to-day use are found in the Esoteric Buddhist and Shugendo worlds my elemental interests have drawn me to. My first awareness of this was in 2016 when a friend in Melbourne translated a Buddhist poster that had several five-element stupa (J. gorinto) on it. While there were some specialist head-scratching kanji involved, her translation led me to Zentsuji, the 75th temple on the Shikoku pilgrimage where Kukai, the founder of Shingon Buddhism was born. More recently, through my blog ‘elementaljapan’, I have had the pleasure of meeting Riko Schroer who translates Shugendo and Buddhist texts that are extremely relevant to my exploration of the elements in Japan. Specialist translators like Riko are a god-send.

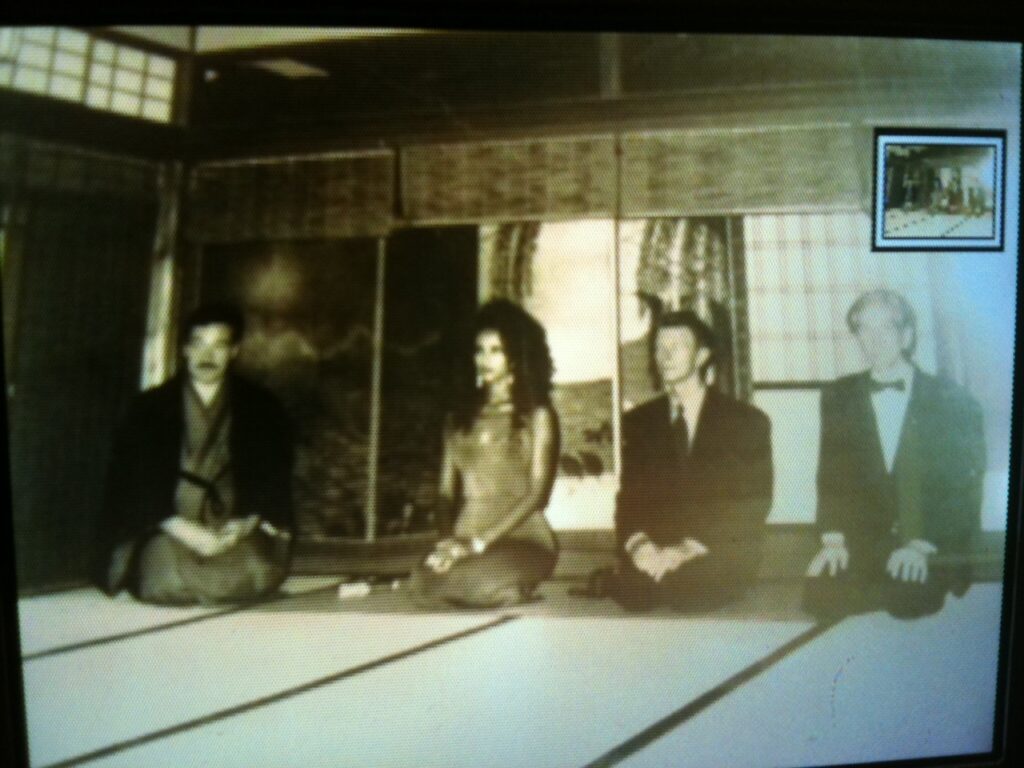

Another life-changing connection made through my blog, and WiK, has been with Yoshiaki Yagi, a gentleman in his 70s who delights in sharing his knowledge of Japanese culture. He lives with his wife Michiko-san in Minoh City, in north-western Osaka Prefecture. Yoshiaki-san contacted me after reading a post on the tea ceremony that I had shared on the WiK Facebook page. Since that time, he and his wife have taken me to many sites in Kyoto and Osaka that I otherwise wouldn’t have experienced. Their generosity and hospitality is wonderful. When Yoshiaki-san invited me to edit the English translation of his upcoming bilingual book Things Japanese – an Invitation to Japanese Culture it was a great honour. He had taken on the monumental task of translating the Japanese to English himself. Through the editing process I have learnt much about ‘things Japanese’, through the eyes of Yoshiaki-san. The book is due to be published soon due to his diligence and determination.

It might be considered blasphemous, but I have found Google Translate a useful tool with written Japanese. In particular, the ability to use the camera on my smart phone to translate Japanese in situ, and to be able to hand-write kanji as an aid to translation, have come in handy several times. While the automated translations of Japanese text have to be treated with caution, generally they are better than no translation at all. New Apps like DeepL are improving the quality of translations available. Whatever program is used in FaceBook though, could do with lots of assistance.

Language is an essential expression of cultures around the world. I would love to immerse myself in Japanese publications and appreciate the implications of not being able to read the primary sources. Having learnt hiragana and katakana provides some entry points. This includes my own translation of a short book by Takada Yuko on the water forests of Yakushima, shared on elementaljapan. As for longer texts with more kanji, translators provide me a way to find out more about ‘things Japanese’. Arigatou gozaimasu. Your names should be on the front covers of books, along with the authors, which has not always been the case. Your work sits proudly among my extensive library of English publications on Japan. In addition to all of this reading/’head-work’, I write blogs with an invitation for feedback, consult with specialists and practitioners in respective fields of interest, and gain insights by living in Japan for half the year – something that has been thwarted by COVID since late 2019.

If a magic wand was at hand (or it was possible to instantaneously comprehend Japanese like Neo in the Matrix learnt new skills!) the first books I’d read are the series by Hiroko Yoshino on ‘Yin Yang and the Five Elements’ (J. inyo gogyo) in Japanese culture. While there is some scepticism in the academic community about her ideas, I would love to see what she says first hand. My plan is to show one of her books to a translator or two from Writers in Kyoto when I’m next in the ancient capital. I am so looking forward to returning to Japan to continue my elemental explorations when the border re-opens.

Recent Comments