An original story by Marianne Kimura

Mr. Nomura had a habit of taking his bicycle and visiting Buddhist temples around Kyoto on fine Sunday afternoons.

He had been to Shodenji before, a perfect little jewel of a Buddhist temple, famous for its simple charcoal brush painting of ten monks walking up and down an invisible crescent-shaped hill. Their black robes are ragged and wind-blown, their legs and feet bare and large straw hats covered their heads.

Shodenji was traditionally a monks’ training ground and it follows the Buddhist school of Rinzai Zen, with its emphasis on kensho, which is defined as “seeing one’s true nature”. Wisdom is to be gained within the activities of daily life.

So the walks and training grounds, up and down the hills around Shodenji, had been places for monks to spend their daily lives attaining wisdom as they went about their tasks.

But on that fateful day in the middle

of September, he had decided to take a stroll around the temple’s bamboo

forest, set slightly to the east of the main hall.

But when Mr. Nomura got to the top of

the hill where the bamboo forest spread out unevenly off a dirt path, he froze

in his tracks.

A tiny barefoot girl dressed in a red

kimono as if for her 7-5-3 ceremony, was dancing in graceful, wheeling circles

around the bamboo trees.

She was not nearly tall enough to be

a three-year old.

She was the height, Mr. Nomura

thought, of a one-year old, if that, and slender and graceful as a sasa leaf.

Mr. Nomura wondered if she was a

robot being filmed for an ad. Her red kimono and the green trees in the dappled

September sunshine made a stunning contrast, and Mr. Nomura looked around for a

movie crew, but he saw only a few finches and sparrows fluttering about.

Suddenly, the girl spotted him. She

stopped dancing and stared directly and gravely at him. Life flickered in the

dark pupils of her eyes, not machinery at all.

She walked shyly up to him and

stretched her tiny arms up.

“Watashi no otousan ni natte kudasai!”

Please be my daddy!

She spoke perfect, elegant Japanese.

Mr. Nomura’s heart warmed to the idea.

He and Mrs. Nomura had no children though they had wanted them long ago.

Now, although he and Junko were both nearing their sixties came the fleeting thought:

Finally,

a baby! How pleased Junko will be!

Dutifully, he hushed his mind.

This

is not your child.

He picked her up and carried her up the wide stone path that led to the main hall. She was as light as a young cat and nestled with perfect poise in the crook of his elbow.

At the entrance to the main hall, Mr.

Nomura peered into the dark tatami-mat ante-room on the right.

An aged, bald monk in a dark brown

robe slid open the glass window.

“Excuse me”, said Mr. Nomura, feeling

odd as he held up the girl, “but is this your child?”

“No”, said the monk. Then after a short,

uncomfortable pause he asked “Isn’t she yours?”

“Well, actually, no,” said Mr.

Nomura, “I found her in your bamboo forest just now.”

“Well, in that case……”, the monk

started to advise.

“I’m hungry, daddy! Let’s go home!” interrupted

the little girl, tightly hugging Mr. Nomura around his neck and wailing, “Kukki

tabetai!” I wanna eat some cookies.

“…maybe call the Child Welfare

Department”, finished the monk looking confused, his voice trailing off as he slid

the glass window shut.

Mr. Nomura carefully carried the

child down the hill. When they reached his bicycle, he set her down, and took

off his blue cotton twill jacket to make a cushion in the front bicycle basket.

Then he lifted her in. It was a perfect fit. She sat with her legs slightly

bent at the knees and smiled, looking happy and comfortable.

He reasoned that he ought to at least

take her home and feed her before calling the Child Welfare Department.

Mr. Nomura rode slowly and carefully

so as not to jolt his tiny and adorable passenger. When they got home, dusk had

fallen and a large full moon was rising over Mt. Hiei to the east.

He opened the front door.

With Himeko still wrapped in his arms,

he called out, “Tadaima”.

Junko Nomura, sitting at the kitchen

table and working a kanji crossword

puzzle, looked up in surprise. The girl stretched out her hands to the woman.

“Okaasan!” Mama. She spoke contentedly, as if recognizing Mrs. Nomura from somewhere

else long ago and far away.

Mr. Nomura explained how he’d found

her in the bamboo forest of Shodenji.

“We’ll have to call the Child Welfare

Department tomorrow”, he said, “but it must be closed now on Sunday evening.

Besides, she’s hungry.”

“Yes”, said Mrs. Nomura, smiling, “By

the way, what is her name?”

“Himeko”, said the little girl primly.

“She is a princess, a hime!” exclaimed Mr. Nomura, a little giddily.

Soon the family was eating a lovely

dinner of rice, miso soup and grilled tai, red snapper.

Omedetai.

Congratulations.

Mrs. Nomura had bought the red snapper

earlier that day.

She laughed. “It’s juugoya!”

The full moon of September, the

Harvest Moon.

“How lucky!” exclaimed Mr. Nomura.

The next morning, Mr. Nomura phoned

the Child Welfare Department and a middle-aged female caseworker arrived and

moments later drove a bawling, sobbing Himeko away in a small white Kyoto city

government-issue car.

That afternoon, there was a call.

“She keeps insisting that she is your

daughter”, said the caseworker to Mr. Nomura, “also, we have no record of any

missing child fitting her description anywhere in Kyoto or Japan. To tell you

the truth, she refuses to eat or drink a thing and she does nothing but cry, so

for her own safety, we would like you to keep her for a few weeks if you don’t

mind.”

Overjoyed at this news, the Nomuras

were told that they would be given, after six months, provisional permission to

adopt Himeko, as long as no one came forward and claimed her.

The Nomuras adopted Himeko and on that day also she received a legal birth certificate. It was estimated that her age, based on her verbal and intellectual abilities, was around three or four. The Kyoto city government set her birthday as September 15, the date Mr. Nomura had found her in the bamboo forest. With this legal birth certificate, she was added to the family registry and thus allowed to start kindergarten.

She ate very well – muffins, chocolates, apple pie, potato chips and mochi rice cakes among many other food — and within three months reached a normal size for a girl of her age.

Years passed like the clap of a pair of hands, and it became time for elementary school.

Mr. Nomura was later to remember

Himeko’s school years as the happiest years of his life. She made friends

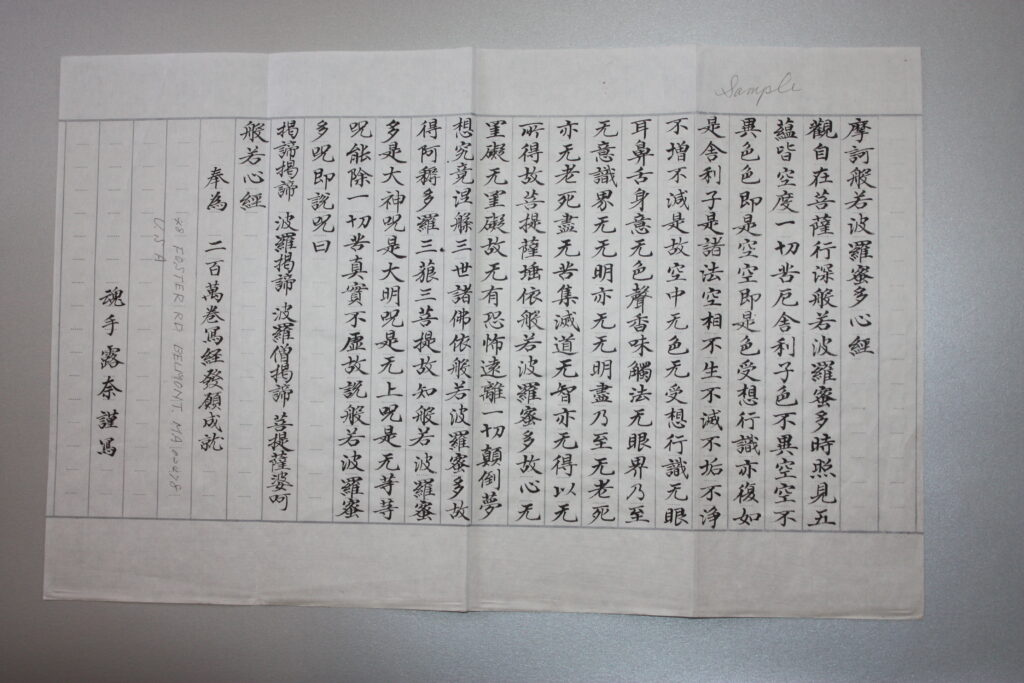

easily, got good grades and enjoyed writing calligraphy.

Himeko liked the pet rabbits, two

lank males named Kuro and Poppo, kept in large wire cages outside the school

buildings, and always volunteered to feed them.

“Why only the rabbits, dear?” asked

Mrs. Nomura. The school also had several pet chickens and even an elderly

little she-goat.

But Himeko only smiled mysteriously.

As the years passed and Himeko started

high school, she became known for her beauty, her intelligence and her modesty.

In her last year of high school, she took the entrance examination for Kyoto

University and received the highest marks ever recorded since the school was

founded in the Meiji era.

She chose astronomy as her major and

proceeded to ace every class, startling the professors with her insights and capability.

She cut a graceful, almost ethereal

figure on campus and seemed almost to glide down the paths, rather than walking

in an ordinary human manner. Her skin glowed with the pale almost luminous light

of starry skies.

Her lustrous long black hair she wore

loose like a maiden in a Heian court.

Many students at Kyodai were captivated

by her elegant bearing and shy yet somehow regal, almost antique manners.

There was something so watchable about her that she was even scouted as a model, but she rebuffed the agency.

Kousuke Kitamura was the young scion of a wealthy Osaka family which was a majority stock owner of one of the sogo shoshas, the massive, politically well-connected conglomerates with subsidiaries that handle banking, finance, oil, petrochemicals, real estate and construction.

One day, after their class on Astrobiology and the Search for Extraterrestrial Life, he summoned up his courage and hesitantly asked her out.

Himeko listened to his stammering plea with a strange impersonal half-smile. Kousuke had to fight with himself not to drown in the pellucid midnight depths of her dark eyes, turned on him without warmth but mesmerizing all the same.

Was

she a snake woman? Was she a witch? Was she a yokai?

As well as admiration, these kinds of fantastic rumors followed Himeko around: little jokes and off-hand comments. Kousuke set no store by these. He imagined they were forged by those jealous of Himeko’s brilliant academic talent and haunting beauty.

In the end, she hesitantly nodded “yes”

to the date and her lovely features even relaxed into a little prim and

encouraging smile.

Kousuke, beaming, was over the moon.

They went to the Kyoto University

Museum, which had an exhibit of prints by Hiroshige.

“Did you like it?” Kousuke asked

Himeko afterwards.

“Yes”, she said, “did you?”

“Well, sort of. Nature in those days

was beautiful, but it is unrealistic to live like that, in wooden shacks with

no electricity. Walking everywhere on foot must have been exhausting too. And I

doubt those straw cloaks kept people dry.”

“I think that lifestyle was perfect. I’d prefer it vastly”, said Himeko sadly, “as real, honest beauty is always to be preferred.”

“Really?” gasped Kousuke. He had to admit he was disappointed to hear it. She seemed to him to be a bit crazy.

Maybe she was a yokai after all?

“Truth is beauty and beauty, truth”, she

intoned, a bit cryptically.

“What on earth are you talking

about?”

“….anyway, how do you know the straw

cloaks don’t work unless you try them?” she asked.

Irritated, Kousuke contemplated not

asking her out on another date, but it was her own beauty which proved

irresistible to him, even when he set it against the convenience of the

lifestyle provided by concrete, plastic and petroleum, the very products his

family dealt in.

And so he did ask her out again,

after their next Astrobiology class.

With a cold and remote look, she put

him off with an obvious excuse: “I’m too busy”.

It was around this time that an

incredible thing happened.

Simon Tusk, the famous IT entrepreneur,

had sent a robot to Mars a few years back, in order to do preparatory

exploration for purposes of human colonization of the Red Planet.

Now the space capsule containing the

robot landed, flawlessly, at the Tusk Space Center in Arizona and its special titanium

specimen collection boxes were retrieved from the capsule’s hull and opened.

In one box, Tusk’s scientists found a

mysterious faintly rose-colored gauzy filmy ghostly swaying thing. It reminded

everyone of seaweed, but more numinous, nearly transparent.

It almost seemed to be alive.

One scientist tried peering at the

pink filmy thing through a special optical lens and cried out incredulously.

Others tried the lens as well and

were equally amazed. The pink filmy ghostly thing had resolved into a tiny

person, about 30 centimeters high. Tusk’s scientists had discovered the Earth’s

first space alien.

Incredibly, seen through the lens,

the alien (it seemed to be a “he”) was dressed like a ninja, in a dark indigo

close-fitting outfit, and could communicate in perfect Japanese.

The space alien told them that his main

colony was actually on the moon, but he had been sent on a solo mission to look

for their lost princess. Only he had gotten lost, and ended up trapped in a deep

Martian crater, until Tusk’s robot had collected him

The media was informed and

sensational headlines on the space alien dominated the news for weeks.

Scholars of culture and history wrote

learned papers speculating on the connection between Japan, a country with

ninjas, and the moon. One revisionist historian was quoted as saying “it would

be more accurate to say that the famous ‘Rising Sun’ flag is instead depicting

the ‘Rising Full Moon’” and gave many convincing reasons for his thesis.

In Tokyo, a rascally reporter asked the Japanese Prime Minister, “Does the flag portray the sun or the moon, sir?” and the Prime Minister skillfully evaded the question by saying both were found in the sky.

On the Twittersphere, #SunorMoon

trended for weeks.

Meanwhile, back in Kyoto, Himeko was

becoming more and more lost to the world. She spent hours reading the news

about the mysterious alien, stopped attending classes, and refused to talk to

anyone except Mr. and Mrs. Nomura.

They were over 80 and quite frail. Still,

they were worried about their daughter, who seemed, oddly, to be shrinking slightly

every day.

“Do you suppose,” Mr. Nomura asked

Junko, “that our Himeko is the famous lost space alien princess?”

“I’ll ask her tomorrow”, promised

Mrs. Nomura.

But that night, it was the full moon. Mr. and Mrs. Nomura were lying on their futons and heard festive music, flutes and drums, outside in their small garden. Mrs. Nomura pushed aside the wooden shoji doors to look outside and saw Himeko, now doll-sized again, dressed in a luminous white kimono and gliding along in a somber procession of Heian courtiers on a magical and glittering road of rose-colored stars that seemed to stretch forever into the dark cloudless sky, all the way to the shining, perfect Pink April Moon.

***********************

- “Pink Moon” is a name for the full Moon around the time of April, when the moss pink, or wild ground phlox, is in blossom.

For more by Marianne Kimura, please see her story of Last Snow,; an account of how her second novel, The Hamlet Paradigm, was taken up by an independent publisher; her double life as academic and fiction writer; her third prize winning entry for the Writers in Kyoto Competition; an extract from a work in progress, Seven Forms of Infiltration; an interview with her about goddesses and ninjas; or an extract from her first novel, The Hamlet Paradigm.

Recent Comments