The judges were reminded of their early days in Japan, when abundant advice was offered by those who had arrived years prior. Some, however, felt that they were stepping into an unknown world as they would probably not visit the type of bar described. The “young and casual” nuance stood in contrast to many more traditionally-focused submissions.

– Karen Lee Tawarayama

*************

ANABA

by Kristin Osani

Not for the first time since we sat down for lunch, I launch my map app so my friend can show me where to look later tonight for this bar she’s raving about. I save a pin in the general Kiyamachi-Pontocho neighborhood north of Shijo and label it anabar, allowing myself an indulgent giggle at the play on the Japanese for hole-in-the-wall.

“It seriously is a hole.” My friend, all excited, doesn’t even pause to commend me for my genius pun. “It’s in this stunted little apartment building, up a couple flights of rickety old stairs. Look for the duct tape doorknob. Or I guess feel for it, the one bare lightbulb in the stairwell doesn’t illuminate shit.”

“Sounds like a great place to get murdered.”

She snorts, crunches a daikon pickle between her teeth. “It’s about as big as this—” She leans one hand back on the tatami and twirls her chopsticks around the ten-square-meter room. “—but super minimal. Bare concrete, LED lights on the walls, booze right on the counter. I wanna say there are like four stools, and a bench-thing in the back by a window covered in this ratty-ass sheet. There’s no menu, you just tell the bartender what you want, and as long as he has the stuff he’ll make it for five hundred yen.”

“Cheap as.”

“Oh, and then dude, you get the drunken munchies, you gotta go down the street to this killer ramen place.” She moans hungrily, as if we haven’t just gorged ourselves on obanzai, and motions for me to pull my phone out again.

Only a few months into my relocation to Kyoto and she’s given me a list longer than the Kamo River of places I gotta check out.

If I can find them, anyway.

Page 34 of 65

The judges found that it was easy to step into the mind of the photographer. A moment of silence and contemplation is provided for the reader.

*****************

Capturing the Zen Spirit

by Michael H. Lester

Since a bamboo grove is relatively open and airy, you can get lost in one only if you put your mind to it, which is (figuratively speaking) precisely what I plan to do.

On a visit to Kyoto, I load my camera equipment into the car and set out before dawn for Arashiyama Bamboo Grove. I hope to get a photograph there without a gathering of open-mouthed tourists crowding the steps through the grove.

morning light

filters through the bamboo—

a stray skylark

Lifting the collar of my jacket against the chill, I place my camera on a tripod, adjust the settings, and wait for sunrise. A Zen-like sense of well-being sweeps across my body in this mystical place.

After having taken several atmospheric photographs of the bamboo grove, I head over to the nearly 800-year-old Tenryu-Ji Temple where I hope to be lucky enough to capture a photograph of the spirit of Emperor Go-Daigo.

a cormorant

dips its head in the pond—

my shutter clicks

Authors who belong to Writers in Kyoto

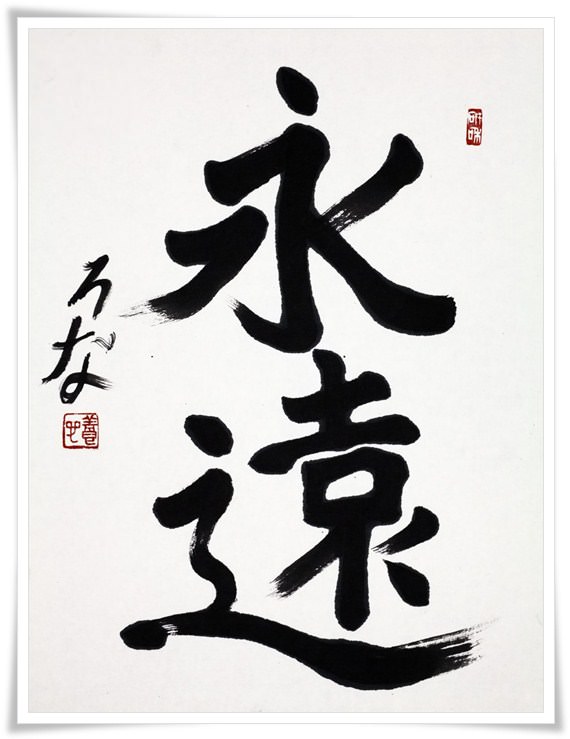

Introducing Rona Conti

WiK welcomes new member Rona Conti, known for her calligraphy. The passages below are extracted from a longer account, ‘Encounters with Brushes Part One‘.

About Rona Conti

Rona Conti is a painter and calligrapher whose artwork is represented in numerous public, private and corporate collections and museums in the United States and internationally. English editor for Beyond Calligraphy, in 1999, she began studying Japanese calligraphy with (Mieko) Kobayashi sensei of Gunma from whom she received her pen name (魂手恵奈). Invited to exhibit calligraphy at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Art with the International Association of Calligraphers for the last five years, she received the “Work of Excellence” Prize three times. She was invited to demonstrate Japanese Calligraphy at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in 2009. Her handmade paper artwork is produced in New York City at Dieu Donne Papermill.

***********************

Dreaming Japan eons before I ever set foot on its soil, from the time I was in college studying ceramics and painting I was mesmerized by Japanese scrolls, the essential black and white mysteriously beautiful forms brushed upon tactile surfaces, then mounted and hung in soft-lit rooms of museums. Envisioning Japan from books and objects, I dreamed of studying calligraphy in its proper setting.

The resumes of Japanese Calligraphy Masters usually start with the young age at which they began their studies, often with a relative. As a Western counterpart, I can only point to my parallel path, my taking up of a different kind of brush. The desired image of my five-year old self, painted with oils on an un-stretched canvas, somehow miraculously survived. It was painted at the studio of my aunt, Helen Jacobson, a fine painter and a beautiful woman. She was blond haired and blue-eyed, always elegantly dressed, I was brown and brown. Vividly remembering painting in her cavernous space where my imagination soared, I decided at that moment my future path. Wishing to be an artist ballerina when I “grew up”, the incongruity of painting in a tutu never occurred to me.

……….

Love and youth has a way of re-shaping dreams. Had I not found the former and not been the latter, I likely would have found a way to adventure to Japan at that time. Instead, I received a letter from Japan from my friend and advisor at Antioch College, Karen Shirley, a potter three years my senior, my “senpai”. “Be sure to come to Mashiko and see Japan before all of the wood burning climbing kilns are no longer allowed because of pollution.” It was 1964. I had graduated that May and was in Boston. I filed her advice away for later and set about pursuing my passion which began with brushes.

……………

Over the years, growing as an artist, the thought of the now rather distant past dream never left. While reveling in color and paint and later exploring work using handmade paper pulps, the vision of Japan continued to come front and center. Dividing the space, placement, the glory of the simplicity of Japanese calligraphy, eliminating the unnecessary and getting to the essence of the black and the white and in between seemed attainable at last. Seeking adventure, finding a way, I secured a job teaching English, sold my car, rented my apartment, told my two creative projects, now 28 and 23, to come and visit, and I departed for Japan. It was summer, 1998.

While I spoke no Japanese, while it took quite a lot of work to convince my bosses that I could teach and study, thanks to an adult student, I found a calligraphy Master willing to teach me. It was March of 1999, I had only three months left on my work visa.

The most precious moment held forever in memory was of holding a brush for the first time in Kobayashi Sensei’s studio, the long journey only just begun. It was the first, but definitely not the last time in Japan that quiet tears of joy would travel slowly down my cheeks. I was home.

by Karen Lee Tawarayama, Competition Organiser

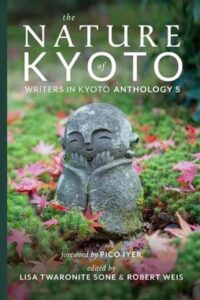

The judges of the Fifth Annual Kyoto Writing Competition are delighted to announce their decisions.

This year, despite the unprecedented challenges posed by the Coronavirus pandemic, we received an impressive number of submissions from countries and regions throughout the world. Several included mentions of the unique situation, and we felt that this was a poignant representation of the times. We are thankful that the virtual nature of this competition provided a means for individuals of several nationalities to express their continued love for Kyoto and Japan, even if currently unable to visit in person. This is a strong indication of Kyoto’s strong international appeal, though it should be noted that the judges were unaware of the names or nationality of those involved.

The winners of the Fifth Annual Kyoto Writing Competition are as follows.

First Prize:

“December” by Lauren E. Walker

The judges appreciated the feminine quality of this piece, which was evocative and skillfully recreated a moment in a person’s life. Residents of Kyoto who have had the pleasure of visiting the Ohara area would be able to imagine the story clearly, based on their personal experiences there and the vivid descriptions.

Second Prize:

“Sparrow Steps” by Amanda Huggins

This was a lovely depiction of a flickering relationship whose end was nigh, although one of the couple did not realize it yet. The overall sadness of the piece tugged at the judges’ heartstrings. Though it might have taken place in any setting, it was the “skeleton of a dry cherry leaf” and autumn showing that “death could be beautiful” that belied a more than passing acquaintance with Japanese literature. The judges also felt that the contrast depicted between the evanescence of sparrows compared to their steps caught forever in cement had a particular “Kyoto flavor”.

Third Prize:

“Interlude: Kyoto” by Brenda Yates

An evocative journey, including vignettes of Kyoto’s four seasons in keeping with Japanese literary and artistic traditions. Nature and human life are skillfully woven together through these images.

Local Prize:

“ANABA” by Kristin Osani

The judges were reminded of their early days in Japan, when abundant advice was offered by those who had arrived years prior. Some of us, however, felt that we were stepping into an unknown world as we would probably not visit the type of bar described. The “young and casual” nuance stood in contrast to many more traditionally-focused submissions.

USA Local Prize:

“Capturing the Zen Spirit” by Michael H. Lester

The judges found that it was easy to step into the mind of the photographer. A moment of silence and contemplation is provided for the reader.

Honorable Mentions:

- “The Sky Shrine” by Joanne Carmen Rasul Binti Abdullah

- “The Winds of Kyoto” by Wim Vanderbauwhede

- “Turn of the Century” by Martin Rice

- “The Bell” by Allen S. Weiss

- “Signs of the Times” by Craig Hoffman

- Untitled by Angiola Inglese

Congratulations to the winners, and our deepest feelings of gratitude to all those who took the time to submit their writings on the ancient capital. Plans are underway to hold another writing competition in 2021. We look forward to receiving your submissions again at that time. A call for entries will be published on the Writers in Kyoto website in mid-Autumn 2020.

We wish for everyone’s health and safety, and hope that we will have a chance to meet again in Kyoto very soon.

Writings about Kyoto, whether by Japanese or foreign observers

Alan Watts on Kyoto (1)

In his autobiography, In My Own Way(1972), Alan Watts writes of having a curious affinity with Japan even in his childhood. His early impressions were shaped by Lafcadio Hearn through Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan (1894), and more substantially through Gleanings in Buddha-Fields (1897).

The first marriage of Watts to the daughter of Ruth Fuller Sasaki gave him an important link to Zen in which he took a strong philosophical interest, though his autobiography makes clear he was never a follower or practitioner. In all, he visited Japan four times and, unsurprisingly, was drawn to Kyoto as the heart of the country’s traditional and religious culture.

Interestingly Watts reserves his time in Kyoto for the very last chapter of his book, entitled ‘The Sound of Rain’. It’s indicative of how special the city was for him. Like Truman Capote, he notes the cheerful sound of the ever-present streams running through and under the city.

(The following four paragraphs are taken from pages 340-342 in the 2001 edition of his autobiography, published by the New World Library.)

*******************

But it was not only for Zen that I went immediately to Kyoto when I first arrived in Japan. I wanted to feel the everyday life of a city which had been soaked in Buddhism for so many centuries, not analyze it like a psychologist, categorize it like an anthropologist, or study its splendid monuments like an antiquarian. I went to gape like a yokel and simply absorb its atmosphere. We went to the district of Higashi-yama, or Eastern Hills, where buildings on narrow, winding streets overlook the rest of the city, which – unusually for Japan – are laid out in the flat grid pattern of an American city in a geographical setting which slightly resembles Los Angeles. Hills, even mountains, lie to the east, north, and west, while the south is open to Osaka, Kobe, and the sea. As in Los Angeles, the best land is in the foothills, where spring-water flows into garden pools through bamboo pipes, and though there are here many quiet and sumptuous private homes, much of the area has been occupied by temples and monasteries. Originally it belonged to feudal brigands, who were scared of the Zen priests because the priests weren’t scared of them, became pious Buddhists, and made generous offerings of land.

When one goes to a city like this it is all very well to make plans to see the famous sights, but there should be plenty of time to follow one’s nose, for it is through aimless wandering that the best things are found. We stayed in the ryokan, Japanese style inn, on the hill above the Miyako Hotel. To the north-west the sweeping grey-tiled roofs of the Nanzenji Zen temples float above dense clusters of pines, and to the southeast stands the huge cathedral of Chion-in, and all about are wayward cobbled lanes enclosed by roofed walls with covered gates, giving entrance to courtyards and gardens, and interspersed with small shops and restaurants. It was April and under such a gate we took refuge from a sudden shower. The door opened a few inches, and out came a hand proffering an umbrella, and as soon as we took it the hand was withdrawn and the gate closed. The umbrella was a kasa made of oiled paper– a wide circle spread out like a small roof supported on a cone of thin bamboo struts, almost as cozy as carrying your own house with you in a quiet, heavy rain. We returned it the next day.

Gutters were bubbling, and water was spilling from bronze, dragon-mouthed gargoyles at roof corners. Everywhere the soft clattering of wooden sandals like small benches with legs on the soles to keep your feet above water. courtyards with glistening evergreen bushes and floating branches of bright green maple. The smell of Japanese cooking – soy sauce and hot saké – mixed with damp earth and the faintest suggestion, pleasant in that small a dosage, of the benjo or toilet which, because of the diet, smells quite different from ours. Because I need a dictionary to read most Chinese characters the signs on shops are just complex abstract designs, or it seems to me that ‘Mr Matsuyama’s Cafeteria’ is the ‘Pine Mountain Harmonious House.’ going deeper in the city we found the long, busy lane of Teramachi, or Temple Street, to nose about in the higgledy-piggedly of tiny shops that sell utensils for tea ceremony, incense, ink, writing brushes, old Chinese books, fan, Buddhist bondieuserie, and huge mushrooms that should be wearing pants– the whole lane buzzing and rattling with motorcycles and diminutive Toyota taxis.

With sense of time gone awry from travel by jet, I wake at four in the morning to hear what is, for me, the most magical single sound that man has made. It comes from a bronze bell some eight feet high and five feet in diameter, struck by a horizontal swinging tree-trunk, and hung close to the ground, actually more like a gong than a bell. it doesn’t clang out through the sky like a church bell but booms along the ground with a note at once deep and sweet and vaguely sad, as if very very old. It sounds once and, when the hum has died away, again… and several times more. From the direction, I realize that this is the bell of the Nanzenji Zen monastery, signifying that, so long before sunrise, some twenty young men, skin-headed and black-robed, have begun to sit perfectly still in a quiet dark hall. When the bell finishes they will begin to intone, on a single note, the Shingyo, or Heart Sutra, which sums up everything that Buddhism has to say – ‘What is form that is emptiness, what is emptiness that is form.’ Actually the language is the Japanese way of pronouncing medieval Chinese, which hardly anyone understands, and the words are chanted for their sound rather than their meaning.

Writings about Kyoto, whether by Japanese or foreign observers

Daniel Ellsberg in Kyoto

An intriguing blog entitled Ten Thousand Things from Kyoto carries an article suggesting that a chance encounter in Kyoto had world-changing repercussions.

The meeting concerned Gary Snyder and Daniel Ellsberg, whose name is famous for the Pentagon Papers that in 1971 exposed US military decision-making in the Vietnam War and which played a decisive role in helping to end the fighting.

The piece runs as follows:

Daniel Ellsberg tells the story of meeting activist, poet, and Zen practitioner Gary Snyder by chance at a bar near the Zen monastery of Ryoanji in Kyoto, Japan, in 1960. Ellsberg was living in Tokyo, working on nuclear weapons policy for the Office of Naval Research, through the Rand Corporation. Snyder was then midway through a nearly ten-year period of Zen practice, staying at or near Zen monasteries for the bulk of that time.

Ellsberg had gone to see the Zen garden at Ryoanji because he had read about it in Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums in which Snyder was the lightly fictionalized major figure.

The impact and memory of Ellsberg’s conversations with Snyder at the bar and the next day at Snyder’s cottage, Ellsberg later reported, played a significant role in his later decision, some nine years later, to divulge the Pentagon Papers, the secret history of the planning of the Vietnam War. Ellsberg’s action was a major contribution to the turn against the war in public opinion and political discussions in the United States.

Writings about Kyoto, whether by Japanese or foreign observers

Pierre Loti on Kioto

Before Lafcadio Hearn, there was Pierre Loti. The Frenchman is (in)famous in Japan for his 1887 novel, Madame Chrysantheme, which influenced the short story Madame Butterfly (1898) by John Luther Long. In collaboration with David Belasco, Long turned the story into a play, which in turn inspired Puccini to write his opera of the same name in 1904. (Later still it would be adapted for the musical Miss Saigon.)

In ‘Travel Sketches of Lafcadio Hearn’, Hiromi Kawashima writes of Loti’s influence on his successor. Hearn was a big admirer of Loti and arrived in Japan just three years after the semi-autobiographical Madame Chrysantheme came out. As well as fiction, the French author also wrote travelogues which include his impressions of Kyoto (extracted below).

Kawashima’s study of Hearn raises the intriguing question of the extent to which a writer should embellish his subject-matter for the entertainment of the reader. Though Hearn himself was unashamedly romantic in his writings about Japan, he became critical of Loti’s excesses and in his final work Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation he sought greater realism and detachment.

*****************

Kawashima writes:

‘Kioto: La Ville Sainte’ [Kyoto: The Sacred Town] is an interesting account of the old city. Loti entered Kyoto by train, and narrates his experience at the hotel, his visit to Yasaka, Kiyomizu, the palace of Taiko-sama, Daibutsuden, Kitano-tenjin, and Sanjusangendo. For his English readers Hearn selected three of the topics. Under the title of ‘In the Palace of Taiko-sama’ he translated Loti’s experience of walking through mysterious chambers. In ‘The Big Bell’ a good natured Japanese family from the country who laughed with Loti are sketched, and Loti says:

What a country this Japan, – where everything is oddity, and contrast!

The third piece, ‘A Nightmare in Daylight’ relates a legion of gods in the gloom of Sanjusangendo. Here Loti exhibits his peculiar ability in description:

In the midst, in the place of honour, – upon the open flower of a golden lotos, vast as the base of a tower, – sits throned a colossal Buddha of gold, – before a golden nimbus deployed behind him like the outspread tail of a monstrous peacock. He is surrounded, guarded, by a score of nightmare-shapes, – something in likeness of human form, exaggeratedly huge, – and seeming to resemble at once both demons and corpses. When one enters through the central door, which is low and sly-looking, one recoils at the sight of these shapes of an evil dream, almost close to one.

We notice that Loti has his favourite vocabulary in dealing with Japan; such as ‘little’, ‘odd’, ‘mysterious’, and ‘strange’. The parts which Hearn chose are very typical of Loti, because Hearn was charmed with his exotic and romantic style. Loti was good at taking in foreign scenes intuitively, and showing them in his inimitable mysterious mood. Hearn tried to convey the deep impression he got from his works, by faithfully translating them. In this sense Hearn’s translations from Loti’s ‘Kioto’ represent the first step towards the travel sketches of Japan by Hearn himself.

**************

Later in his paper, Kawashima adds the following: While Loti remained a traveller to the last, Hearn decided to stay much longer in the country. In 1892 he visited Kyoto and wrote to [his friend] Mason:

… I can’t say that I liked Kyoto as much as I expected. First of all, I was tremendously disappointed by my inability to discover what Loti described. He described only his own sensations: exquisite, weird, or wonderful. Loti’s ‘Kioto: La Ville Sainte’ has no existence. I saw the Sanjusangendo, for example: I saw nothing of Loti’s – only recognised what had evoked the wonderful goblinry of his imagination.

Hearn realised then that Loti’s Kyoto has been the reflection of his sentiments and taste, rather than what Kyoto really was. Visiting Kyoto himself, Hearn found that what had attracted hims was just the image of foreign lands reflected on Loti’s mind. Accordingly I regard this letter as the diverging point of the two writers. Once he failed to see the objects the way Loti had showed him to see them, his admiration began to cool down. New works by Loti seemed to him less fascinating.

Writers in focus

Alex Kerr Reminisces

(The following article first appeared in Echoes: Writers in Kyoto Anthology 2017)

Three Old Men of Kyoto

by Alex Kerr

Harold Stewart

David Kidd

William Gilkey

I don’t know if young men are like this any more, but I was the sort of young man who sat at the feet of old men. I hung on their every word, even writing down scraps of conversation like Boswell did with Dr. Johnson. And fate was kind to me, because it sent me three amazing old men in Kyoto: They were David Kidd, William Gilkey, and Harold Stewart.

All three were formed by dramatic events in their youth, events which propelled them in the end to Kyoto.

Harold Stewart, The Poet

Harold Stewart (1916-1995) was one of those unusual people who have lived a previous life completely unrelated to the one they finally choose in later years. An Australian, when only 25 he became famous overnight through a hoax: Harold and a friend created an imaginary poet, named Ern Malley who wrote overblown free-verse and whose poems were supposedly found in a trunk after his death. As a spoof in protest against the “decay of meaning and craftsmanship in poetry,” they sent these poems to the editor of a literary magazine who published them to great acclaim.

When it was revealed that there was no Ern Malley, it led to a scandal as a result of which the editor was fined, critics bitterly argued the merits of free versus rhymed verse, and Harold’s name went down in Australian literary history. He spent the rest of his life writing serious poetry — rhymed and metered, of course.

In middle life, Harold turned increasingly to Asia, beginning first with Bali, where he traveled and lived for a while as guest of painter Donald Friend. Eventually he discovered Japan in 1961, and finally moved to Kyoto in 1966. He was drawn by the beauty of Kyoto as well as the charm of Masaaki, a garden designer who later became the partner for some years of tea master John McGee. Harold was 50 years old when he made his move.

Already having experienced a full life in Australia and Bali, Harold lived in Kyoto more or less in retirement. He devoted himself to the life of a pure literary man: studying Buddhism, taking walks, and writing long poetry and prose cycles, the most important of which was By the Old Walls of Kyoto (1981).

I doubt that there will be foreign Harold Stewarts in Kyoto in the future, as the essence of his existence lay in the way the old city, its history and arts fit in with his contemplative life style. He used to send me manuscripts of poetry now and then, and I find that I still have pages from his epic Autumn Landscape Scroll, which he finished just before his death. I don’t know if it was ever published. As if describing his own life in Kyoto, he relates how the poet Wu Tao-tzu walked into a painted landscape:

The Emperor could not follow where he led,

But only watch his distant figure, dim

And indistinct, diminishing in scale

While passing through the morning’s golden haze

That glorified the foot-hills, veil on veil,

Until beyond their range’s farthest rim

Wu disappeared at last from mortal gaze,

And wandering on through that pictorial plane,

Lost in his work, was never seen again.

David Kidd — The Aesthete

David Kidd (1926-1996) was a colorful, outrageous personality, surrounded by an adoring court of disciples and admirers. There was also an outer ring of those who absolutely loathed him. Meeting David, attired in satin Tibetan robes, with his long golden hair, endless cigarettes, his kang (a Chinese raised platform) on which David reigned while others sat on the floor below him, and his brilliant but stinging conversation, was an experience that none forgot.

Coming from a poor family in Kentucky, David went to Beijing when he was 19 years old — and entered into a realm of fantasy. He married Aimee Yu, daughter of an old aristocratic family, and took up residence in the Yu mansion, a palace of 400 rooms dating to the Ming dynasty. He fled soon after the Communist victory in 1952, but in the meantime — as one of the very last people in history to have seen it — he had absorbed the magnificent life of Imperial China.

After a year in America, he came to Japan and stayed, living first in Kobe, then Ashiya (this time in a daimyo’s palace), and finally, after 1978, in a grand residence on a hill overlooking the Miyako Hotel. With an eye for beauty that was close to genius, David built a fabled Chinese and Japanese art collection, and it was surrounded by gold screens, Ming tables, jade, ceramics, and polished lacquer, that he held court.

David’s true art was conversation. Talk in his palaces adorned with ancient treasure took on a surreal tone. When someone commented that a gold screen looked strangely pink, David would remark “Oh, it’s just the reflection off the red silk covering the Manchu crown.” And if you looked closely, it was.

David was the ultimate aesthete. For David colors were like gems and each color had a taste, such as the peppermint clouds in Ming portrait painting which he called “ice-cream colors.” He insisted that everything should be art, even (as he glanced out the window at his partner Morimoto laboring in the garden) the art of burning weeds. He added, the great thing about burning weeds, unlike ephemeral arts such as flower arranging is, “Once burnt, always burnt.”

David’s humor was completely irreverent, and so infectious that casual visitors would open their hearts and tell him things they wouldn’t tell their closest friends. “I always think a well-chosen word is humorous,” he used to say.

His wit could be sharp, even cruel. A Japanese boy, irritated by David’s harsh criticisms of Japan, once asked him, “There must be something good about Japan. Otherwise, why would you live here?” “Of course there is” replied David. “What is it?” asked the boy. “Japan is wonderful because it preserves so many beautiful Chinese things,” David pronounced.

Within the wit, however, was a kind of Buddhist wisdom, a sense of the mystery and evanescence of things. David saw first the life of old Beijing disappear, and then old Japan. Nothing stayed the same, and nothing was what it appeared to be. One night a group of us were gathered late at night on the moon-viewing platform in the garden of David’s palace in Ashiya shortly before it was dismantled to make way for an apartment complex. Masaaki was there and he commented on the strange blooming of cherry blossoms out of season. “Is that a cherry tree?” asked Masaaki. “Yes,” replied David. “I can see cherry blossoms!” said Masaaki. “Well,” said David, “It’s just like Persian carpets. You’re looking at the pattern that isn’t there. Actually you’re looking at bug-eaten leaves and the spaces look like flowers.”

William Gilkey — The Sage

Of my three old men, William Gilkey (1920-2000) was the least known to the greater world, but had a cult following which may even have rivaled David Kidd’s.

William Gilkey hailed from Chikasha, Oklahoma. Trained at Harvard and Julliard as a concert pianist, he went first to India as a young man, and then, like David Kidd, moved to China in the 1940’s. Living first in Suzhou, and later in Beijing, he was to witness the fall of the old regime, and experience two years of house arrest and Maoist brain-washing, before being deported in 1954. When asked why he stayed on, even though most of the other foreigners fled, Gilkey replied characteristically, “This was the greatest show on earth, and I had a front row seat. How could I leave?”

Arriving in Kobe, Gilkey became fast friends with David Kidd, and the two shared a house for some years before David found his Ashiya palace. But as the years passed, the paths of these two men diverged. In 1969, at the age of 50, Gilkey changed the course of his life. He left Japan and returned to America, where he embarked on a ten-year course of study including classes in professional writing at Oklahoma University, study of health regimens through vitamins, and research into the occult. He read everything from the Bible to Madame Blavatsky, and at one stage visited Japan where he met and interviewed Japan’s leading mystics.

By the time he returned to Japan in 1979, Gilkey had become a mystic and a sage. People called from all over the world to have their I Ching cast; others took up piano under him; and I studied occult lore from Gilkey. Among various useful talents, he taught me how to stop the rain. He himself, however, rarely could be bothered to stop rain — except on laundry day.

With his homey Oklahoma accent, Gilkey would explain occult truths with wit as trenchant as David Kidd’s. Outlining the laws of karma, he would say, “When you do someone wrong, you are creating a powerful karmic link. You should ask yourself first, ‘Do I really want to walk hand in hand down eternity with this jerk?’”

With his bald head, flowing gray hair, and twinkling eyes, Gilkey looked rather like Yoda in Star Wars. He lived in a charming old Japanese house in Kameoka, just outside of Kyoto. There he taught his band of disciples, as sages have done for centuries, the hard facts of life: that all is transient, and that love, beauty, and friendship fail. Yet he remained a romantic who believed that the only correct way to play a piano phrase is to “break your heart”.

Coda

Well, why Kyoto? I doubt very much that these three men would have been attracted by the whirling activity of Tokyo, since their lives were basically quiet ones, devoted to their interests: literature, art, and philosophy. David Kidd used to say, “You need to make your living with your big toe,” meaning that paying the rent should only occupy a small part of your energy. In Kyoto, such a thing is possible.

Another aspect of each of their lives was that time had in fact passed them by. All three dwelled in what amounted to a dreamworld. What happened in Japan was increasingly irrelevant to them, and what they did no longer mattered. And yet there was nothing sad in this. Because of it, they had the leisure to be wise and wonderful.

One is reminded of a paragraph from an old guidebook to Peking, describing the palace eunuchs after the fall of the dynasty:

It is pleasant to look at the brocade of autumn tints from the pretty pavilions on the hillside, to linger near the pond where tame goldfish rise to the surface to be fed at the sound of a wooden rattle, to gossip with lonely old men who have cut themselves off from family life by the nature of their calling, but who served Empresses and princesses and remember many things … Alas, these Manchu grandees — so typical of the faults and virtues of the past — have nothing to offer the new world except a wonderful and unwanted elegance of living which still permits them to accept with calm dignity the fate of failures.

In the end, we’re all failures, of course. David warned, “Life is a constant battle against boredom on all fronts. You must create your own inner cinema.” This these three old men did, and I was lucky to sit at their feet and take notes. None of it is very useful. But it’s still nice to know how a metered couplet should really be written, and what the taste of ruby red is, and how to stop rain.

********************

The following photos of David Kidd’s house overlooking the Miyako Hill are taken from the lavishly illustrated Japanese Style by Suzanne Slesin, Stafford Cliff and Daniel Rozensztroch (pub. Clarkson Potter, 1988).

Japanese Wood and Carpentry, Rustic and Refined

By Mechtild Mertz

(reviewed by Judith Clancy)

Japan is a country whose primary building material is wood.

Walking the old streets of Kyoto or entering a temple reveals the legacy of Japan’s forests: the soothing calm symmetry of wood lattice-fronted homes; and temples with lustrous pillars treated with ancient techniques like the spear-head plane.

Mertz’s book is a slim volume with an immense amount of information, full of color photographs that identify the characteristics of each wood type, and painting scrolls that show the tools that carpenters use to wield their ancient craft.

Wood is the chosen medium for structures and ornamentation in a country that supports craftsmen and appreciates the inherent sensuousness of wood.

The wood also shows the 32 facsimiles, of a little Handbook edited for presenting Japanese wood species at the Philadelphia World Exhibition (1876).

As a woodworker, an ethnobotanist and researcher specializing in Asian religious wooden sculpture and author of “Wood and Traditional Woodworking in Japan,” Mertz draws upon her great knowledge of Japanese culture and society to explain terms, history, and sources for timber by woodworkers.

**********************

Abstract of Japanese Wood and Carpentry

Drawing attention to the wood species used by Japan’s carpenters, Japanese Wood and Carpentry, Rustic and Refined, reveals the ingenious ways in which Japanese carpenters exploit the extraordinary diversity of their country’s forest resources. Its first part introduces four types of Japanese carpenters – temple and shrine carpenters, carpenters of refined teahouses and residences, joiners of doors, windows and screens, and general carpenters – and details the wood species used by each. In its second part, the book grants the modern-day reader access to a rare document: the Yûyô Mokuzai Shôran 有用木材捷覧 handbook, a guide to Japanese wood species prepared by the Meiji government for the 1876 Philadelphia Exhibition. Full-size facsimiles of thirty-two of the handbook’s samples furnish an in-depth look at some of the important wood species used in Japanese architectural construction. Together, the two parts make for an indispensable resource for anyone interested in learning more about Japan’s fascinating ‘culture of wood’.

About the author

After having trained as a cabinetmaker in Germany, Mechtild Mertz took courses in Japanese Studies and East Asian Art History, first at the University of Heidelberg and then at the Sorbonne University. She studied wood anatomy at Pierre-et-Marie-Curie University (Paris) and obtained a PhD in ethnobotany at the National Museum of Natural History (Paris). For over fifteen years she has been a Cooperative Researcher at Kyoto University’s Research Institute for Sustainable Humanosphere (formerly the Wood Research Institute). Since 2018 she has been a Researcher specializing in Asian religious wooden sculpture at the East Asian Research Centre (CRCAO) of the National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) in Paris.

The book is available at:

海青社 英語のホームページ

http://www.kaiseisha-press.ne.jp/cat_en.pl?lang=eng&type=view&RecordID=1558775637

Amazon.com (US)

https://www.amazon.com/dp/4860993675

Writers in focus

WiK titles for World Book Day

A SELECT LISTING OF BOOKS BY MEMBERS OF WRITERS IN KYOTO

*******************

AMY CHAVEZ (non-fiction)

Amy’s Guide to Best Behavior in Japan (Stone Bridge, 2018)

Guide to Japanese customs & etiquette.

Running the Shikoku Pilgrimage: 900 Miles to Enlightenment (Volcano Press, 2012)

First-person account of circling Japan’s Buddhist 88-Temple Pilgrimage route.

Japan, Funny Side Up (e-book, 2010)

A selection of ‘Japan Lite’ columns that appeared in the Japan Times from 1997-2010.

*******************

JUDITH CLANCY (Kyoto)

Exploring Kyoto (rev. edition, Stone Bridge Press, 2018)

Guided walks that explore the city’s cultural wealth as well as its by-ways.

Kyoto Gardens: Masterworks of the Japanese Gardener’s Art (Tuttle, 2015)

A survey of the city’s best gardens richly illustrated by photographer Ben Simmons.

Kyoto Machiya Restaurant Guide (Stone Bridge Press, 2012, rev. ed. Kindle 2020)

An informed guide to dining in traditional townhouses illustrated by Ben Simmons.

*********************

JOHN DOUGILL (non-fiction)

Kyoto: A Cultural History (Signal/OUP, 2006)

Overview of the city’s formative role in Japan’s cultural and artistic development.

Zen Gardens and Temples of Kyoto (Tuttle, 2017)

Guide and cultural background, with photographs by John Einarsen.

Japan’s World Heritage Sites (Tuttle, 2019)

An overview of the country’s diverse cultural and natural heritage, from Shiretoko to Okinawa.

*******************

DAVID DUFF (non-fiction)

Ero-Samurai: An Obsessed Man’s Loving Tribute To Japanese Women (iUniverse, 2005)

A personal and cultural exploration of the spell cast by Japanese women.

********************

JOHN EINARSEN (photography and book design)

Kyoto: The Forest within the Gate (editions I and II)

Photographs by John Einarsen, poems by Edith Shiffert, calligraphy by Rona Conti, as well as essays.

Small Buildings of Kyoto I & II

Photographs by John Einarsen featuring Kyoto’s charming small buildings.

Upcoming: This Very Moment: The Experience of Seeing (2020)

To be published later this year, a collection of Miksang contemplative photographs.

********************

MICHAEL GRECO (comic fantasy)

Plum Rains on Happy House (independently published, 2018)

An absurdist take on communal living in a Tokyo guesthouse.

Assunta (independently published, 2019)

A hurricane strikes a small island community off Texas with unforeseen consequences.

Moon Dogg (independently published, 2018)

A small-time filmmaker’s plan to make an expose of a fundamentalist sect goes weirdly wrong.

***********************

DAVID JOINER (fiction)

Lotusland (Guernica Editions, 2015)

A novel about expat life in contemporary Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

************************

ALEX KERR (Japanology)

Lost Japan: Last Glimpse of Beautiful Japan (Lonely Planet, 1996/ Penguin 2015)

A personal account of cultural aspects that are dying out, first written in Japanese.

Dogs and Demons: Tales from the Dark Side of Japan (Hill and Wang, 2002)

An unwavering look at the environmental and social cost of Japan’s economic miracle.

Another Kyoto (Penguin, 2018)

A unique look at Kyoto through the material with which its cultural heritage is shaped.

************************

REBECCA OTOWA (various)

At Home in Japan (Tuttle, 2010)

Illustrated essays about lessons learned from being wife to the heir of a farmhouse in rural Japan.

My Awesome Japan Adventure (Tuttle, 2013)

A children’s book illustrated by the author about a boy who lives with a homestay family in regional Japan.

The Mad Kyoto Shoe Swapper and other short stories (Tuttle, 2020)

Thirteen short stories, mostly fiction with a few historical or based-on-truth, about people in Japan. Illustrated.

********************

SIMON ROWE (fiction)

Good Night Papa: Short Stories from Japan and Elsewhere (Atlas Jones & Co., 2017)

Fifteen stories high, nine countries wide, and peopled with wily, dim-witted, hapless, strong and gentle characters.

**********************

FERNANDO TORRES (fantasy and historical fiction)

A Habit of Resistance (Five Towers, 2015)

The humorous story of a quirky group of nuns who join the French Resistance.

The Shadow That Endures (Five Towers, 2013)

A curious globe found in an antique store in Scotland contains the key to the multiverse.

More Than Alive: Death of an Idol (Five Towers, 2020)

Forthcoming: A paranormal coming of age novel set in 2042 Japan. *************************

ALLEN S. WEISS (Aesthetics)

The Grain of the Clay: Reflections on Ceramics and the Art of Collecting

An autobiographical account of a passion for Japanese ceramics; photographs by the author.

Zen Landscapes: Perspectives on Japanese Gardens and Ceramics (Reaktion, 2013)

The first study of the relations between landscape and ceramics; photographs by the author.

The Wind and the Source: In the Shadow of Mont Ventoux (State University of New York Press, 2005).

A literary and philosophical study of the famed Provençal mountain.

************************

JANN WILLIAMS (ed.) (environment / Anthology editor)

(ed with I.J. Yates) Encounters with Kyoto: Writers in Kyoto Anthology 3 (WiK, 2019)

A miscellany of writing by 22 WiK members, which includes poetry, fiction and non-fiction.

(ed with R.A. Bradstock and A.M. Gill) Flammable Australia: The Fire Regimes and Biodiversity of a Continent (Cambridge University Press, 2002)

A synthesis of the current knowledge in this area and its application to contemporary land management.

Recent Comments