To celebrate WiK’s 5th Anniversary Celebration today, here is a list of all the activities and talks we have had over the past five years. There have been fun events like our bonenkai showcase of members’ talent, and there have been serious events such as the Heritage and Tourism symposium held together with the Agency of Cultural Affairs. In addition, we have run a website and Facebook pages, as well as hosting best selling and internationally famous authors who have included such luminaries as Karel van Wolferen, Robert Whiting and Richard Lloyd Parry. Over the years there have also been a variety of events, talks and presentations, and our heartfelt thanks go to those who have participated, in particular to all the speakers who contributed their expertise and time. A big thank you too to our committee of Paul Carty (finance/co-chair), Karen Lee Tawarayama (competition), Marianne Kimura (membership), Amy Chavez (social media), Mayumi Kawaharada (Japanese liaison), and Jann Williams (Anthology editor). From small beginnings WiK now has over 50 members and with their support we hope to weather the present Corona crisis and emerge in even better shape.

(NB Just about all the entries below were written up for the WiK website, so by entering the name in the search box, you should be able to locate the report. This listing has been updated to include recent activities held after the 5th anniversary.)

KEYNOTE SPEAKERS

Launch with Amy Chavez on writing in Japan at Roar Pub on April 19, 2015

Robert Whiting on gangsters and culture at The Gael, April 24, 2016

Robert Yellin on a life with ceramics, The Gael April 23, 2017

Eric Johnston on Kyoto Matters, The Gnome April 22, 2018

Richard Lloyd Parry about his books, Omiya Campus Ryudai May 12, 2019

(Online) Jeff Kingston on Japanese politics May 23, 2020

WEBSITE AND FACEBOOK

– interviews with members

– coverage of WiK talks and events

– Kyoto-related writings

– members’ current projects

– new publications and book reviews

ANTHOLOGIES

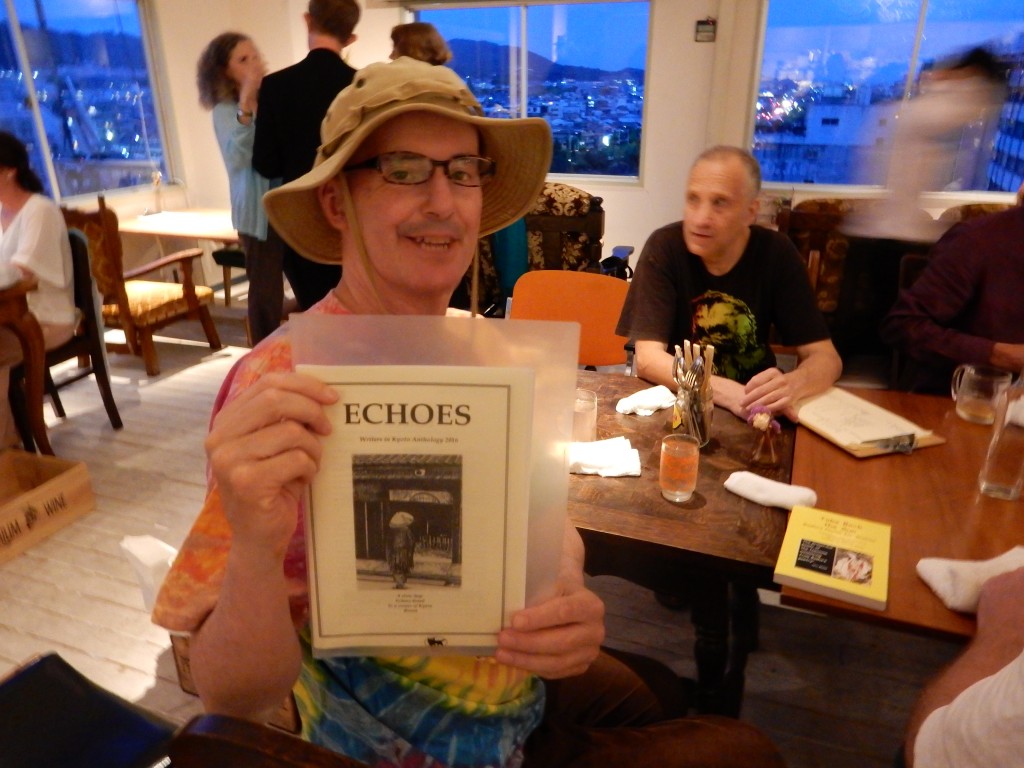

* Echoes: Writers in Kyoto Anthology (ed. Eric Johnston, 2016)

* Echoes: Writers in Kyoto Anthology 2 (ed. John Dougill, Amy Chavez and Mark Richardson, 2017)

* Encounters: Writers in Kyoto Anthology 3 (ed. Jann Williams and Ian Yates), 2019

ANNUAL COMPETITION (run by Karen Lee Tawarayama)

– several prizes for winning entries

– publication on the website

– publication in the WiK Anthology

EVENTS

Words and Music twice a year (June and December) featuring amongst others Mark Richardson, Mayumi Kawaharada, Rebecca Otowa, Ken Rodgers, James Woodham, Ted Taylor, Robert Yellin, Lisa Wilcut, Kevin Ramsden, with improv musicians Gary Tegler and Preston Houser

May, 2015 – meeting with Eric Oey, head of Tuttle

June 12, 2016 – launch of the first WiK Anthology, ed. Eric Johnston

July 25, 2016 – WW1 Readings to commemorate the Somme

Oct 2, 2016 – Alex Kerr’s book launch of Another Kyoto

Oct 28, 2016 – Basho Colloquium with Robert Wittkamp, Jeff Robbins and Stephen Gill

Nov 13, 2016 – Book launch of Marianne Kimura’s The Hamlet Paradigm

Nov 18, 2017 – Book launch of Zen Gardens and Temples of Kyoto by John Dougill and John Einarsen

April 2018 and 2019 – Meetings with Eric Oey, head of Tuttle

June 22, 2019 – Launch with Jann Williams of Encounters: Anthology 3 Umekoji Park, Midori Buil.

Nov 8, 2019 – Heritage and Tourism Symposium with Alex Kerr, Amy Chavez, Murakami Kayo and John Dougill

Nov 24, 2019 – At Home with Chris Mosdell

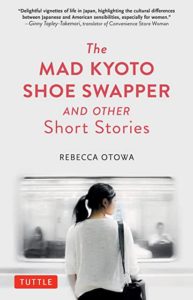

Nov 15, 2020 – At Home with Malcolm Ledger (book launch for The Mad Kyoto Shoe Swapper, Kyoto 100 Sights, and Kyoto: A Literary Guide)

LUNCH / DINNER TALKS

Dinner with Karel van Wolferen (Nov. 8, 2015)

Drinks with Bernie MacMugen on book printing (Dec 11, 2016)

Dinner with Judith Clancy at Papa Jon’s (Feb 12, 2017)

Dinner with Mark Teeuwen at Cafe Maru (March 11, 2017)

Dinner with Norman Waddell (May 21, 2017)

Dinner with Juliet Winters Carpenter at Rigoletto (May 27, 2018)

Dinner with Micah Auerbach ‘Zen in the 1930s’ (March 3, 2018)

Dinner with Jonathan Augustine (Oct 7, 2018)

Lunch with Jann Williams at Khajuraho Restaurant (Oct 28, 2018)

Lunch with Venetia Stanley-Smith at La Tour, Kyoto Uni (Nov 11, 2018)

Lunch with Yumiko Sato on music therapy, Mughal (Nov 24, 2018)

Dinner with Vahina Vara and Andrew Altschul at Kushikura (Dec 2, 2018)

Lunch with Stephen Mansfield at La Tour, Kyodai (Sept 28, 2019)

Dinner with Mark Schumacher at Ungetsu, (Oct 4, 2019)

Lunch with Rebecca Otowa at Ume no Hana, (March 14, 2020)

PRESENTATIONS

Poetry by Mark Richardson and Mark Scott at The Gael (June 21, 2015)

David Duff and David Joiner gave readings at The Gael (Oct 11, 2015)

Allen Weiss reading at Robert Yellin’s gallery, shakuhachi by Preston Houser, (Dec 18, 2015)

Brian Victoria at the Gael on Zen terrorism in the 1930s (Feb 28, 2016)

Allen Weiss reading from The Grain of the Clay at Robert Yellin’s gallery (Dec 4, 2016)

Justin McCurry, Guardian correspondent, at Ryukoku Uni. (May 26, 2017)

Amy Chavez on blogging at Omiya campus, Ryukoku (Oct 1, 2017)

Jeff Robbins lecture on Basho at Ryukoku University (Oct 28, 2017)

Mark Richardson on Robert Frost at Cafe Maru (Jan 21, 2018)

Reggie Pawle ‘Zen, Psychotherapy, and Psychology’ Ryudai (April 14, 2019)

Hans Brinckmann on Kyoto in the 1950s Ryukoku University (Feb 3, 2019))

Robert Wittkamp on Santoka at Ryukoku Uni. (Jan 25, 2020)

Matthew Stavros zoom session on his translation of Hojoki (Nov 22, 2020)

Alex Kerr zoom interview about Finding the Heart Sutra (Nov 29, 2020)

Recent Comments