1) Could you tell us a little bit about your background and your connection with Japan?

My first connection to Japan was through the Suzuki method. I was two and a half, and they had this crazy idea of teaching young children to play musical instruments, but you know something? It worked. When I was a bit older, we had two exchange students from Japan, which led to my lifelong obsession with Japanese food. Finally, as an adult, working as a suit at ABC/Disney, I was assigned to be a liaison for the Power Rangers, whom we had acquired from Saban and Fox. We took the Super Sentai series from Japan and reshot any dialogue scenes using English actors. Many of the costumes, from those years, are displayed at Toei Studios in Kyoto. In 2005, I finally dragged my wife to the Expo in Aichi, and that was the beginning of her love for Japan. A couple of years ago we bought a 120-year-old house near Tofukuji, and that’s when the relationship with Japan became more serious. As we sat in the back room of the bank, drinking tea with the sellers, agents, and scrivener, it became apparent that dating had turned to marriage.

At first, our neighbors appeared wary of us, as we were the first foreigners to move into the neighborhood. The association met to discuss how to handle the difficulties that might result from our arrival. It was the start of a time of rapid change for the sleepy neighborhood. Tourism to Kyoto was exploding, and nearby Fushimi Inari Shrine had become the city’s premier attraction. Many people chose to combine a visit to Tofukji Temple with the short walk to see the vermillion torii gates. Foreigners flooded the street that ran through our sleepy neighborhood. For nine months the renovation of our house dragged on. The previous owner had attempted to modernize the old machiya, and I was determined to restore as much of its traditional character as possible. Finally, Gion Festival arrived. My wife and I dressed in our yukatas to see the yama and hoko making their procession down Shijo street. The head of the neighborhood association appeared from his door to find us not in our usual western attire. He looked us over carefully, and to my surprise, voiced his approval. My wife rubbed his dog’s belly while I described our day’s plans in broken Japanese. Soon, the local sake shop owner, also a member of the neighborhood council, came out with his camera and began to take pictures. As we said our goodbyes and walked to the train station, it was clear that a shift had occurred. We were no longer strangers, but part of a community.

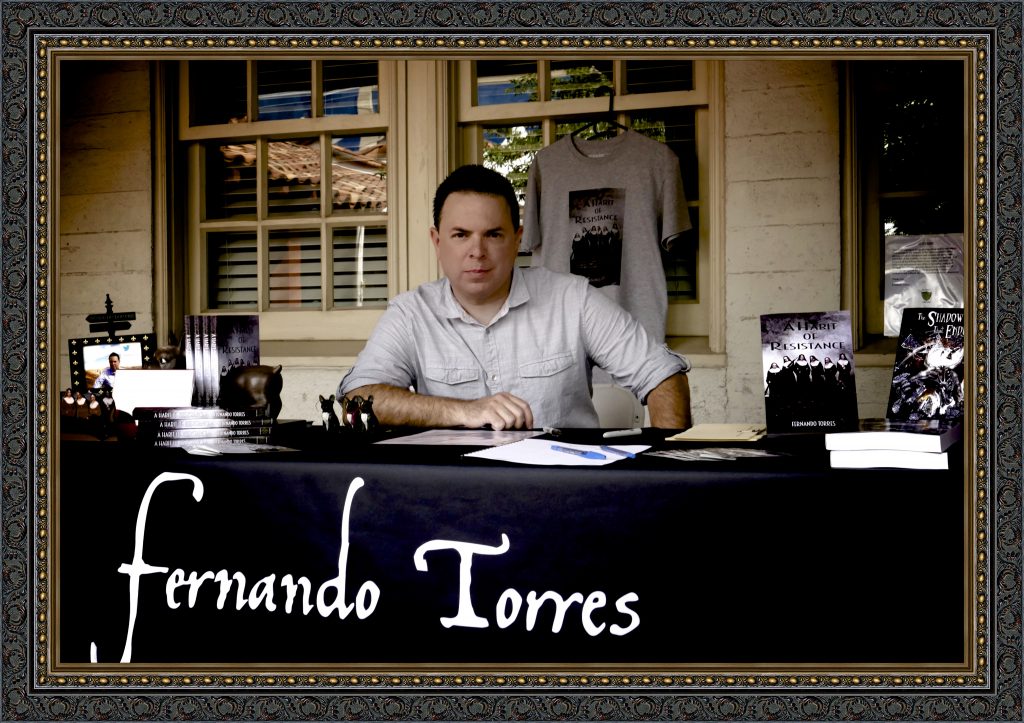

Fernando in his Disney days

2) What is it about Kyoto that attracted you?

I am originally from Los Angeles where we had no actual seasons — unless you count the Oscars. To be in a place where the passing of Summer to Fall occurs with religious sincerity is akin to gaining back a part of my life. It is like Michael Jackson searching for his childhood, but without the lawyers. In all seriousness, few people in Kyoto look forward to the changing of the leaves like I do. Last year, I even denied myself my momiji-gari (the viewing of fall foliage) so that I could appreciate them all the more this year. Local friends were astonished to find me avoiding Kyoto during November, but I said to them, “If I see them every year, I will only begin to take them for granted.” This year I have planted a small maple tree in front of the window near my horigotatsu, and I wouldn’t miss the arrival of its red and orange colors for all the world.

3) What sort of writing do you do?

Good, I hope (rimshot). While I work in several genres, all my work could be categorized as “high concept.” A Habit of Resistance is historical fiction, but the idea of a group of nuns joining the French Resistance is definitely “high concept.” I would not advise other writers to work in as many genres as I do, but there is a continuity of themes that is unmistakable in my writing.

4) What has been the most satisfying moment for you in your writing so far?

Fernando during his interview with TV Tokyo

I was at a book signing in Tuscon, and a college student was practically hyperventilating at her joy of being at my table. I didn’t know quite what to think, but those are the moments that keep you motivated. I also enjoyed talking about my writing with TV Tokyo recently, but I’m not sure how much of that will be present in the final cut.

5) What sort of problems have you faced?

Going from television to fighting for every reader has been a real change in paradigm. It’s difficult to stay motivated when you put forth so much effort only to achieve little comparable results. Feedback from readers is critical. In day-to-day life, my poor Japanese has been a factor, but I am committed to becoming conversational before I’ve insulted every last person in Honshu.

6) What projects are you currently working on?

I just finished the writer’s draft of a novel tentatively called, “More Than Alive.” It’s paranormal sci-fi and takes place in Japan thirty years in the future. Many issues such as privacy, and our virtual lives, are addressed, and it would be perfect for the Japanese market, were it not for my before mentioned Japanese skills. The main characters live in a house based on Ōkōchi Sansō in Arashiyama. I am also looking forward to writing my first nonfiction, the comedic story of buying and renovating our Meiji-era machiya in Kyoto.

7) What are your favourite books or writings about Japan?

I feel the most substantial connection to The Tale of Genji, although I’m still trying to grasp it truly. Every time I see a statue of Murasaki Shikibu I give thanks for what she accomplished and its effect on my life. Another reason is that my house is supposedly on the former location of Hosho-ji Temple, which is featured in the “Boat on the Waters” chapter. I’ve had difficulty confirming this little factoid, so any help from local historians is appreciated.

8) Finally, do you have any message for the members of Writers in Kyoto?

Ultimately I decided to join a writer’s group in Kyoto, rather than Las Vegas, because I related more to the everyday struggles of my fellow expatriates in Japan. Because I live a rather cloistered life, when I am in the U.S., I find myself interacting more with neighbors and friends in Japan. As I passed through Osaka, the other day, I found myself pondering what it even meant for something to be “foreign.” I visited Chicago a few months ago and found myself in a place that seemed exotic and unfamiliar compared to Dotonbori, where I know exactly where to go for the best okonomiyaki. Kyoto is yet more familiar still, and it occurred to me that I haven’t thought of it as being foreign for many years. Perhaps that is why it seemed best to join the Writers in Kyoto, and I look forward to your support and returning it as best I am able.

Fernando at a neighbourhood temple near the house at Tofukuji he has renovated

Leading Shinto scholar

Leading Shinto scholar

Mike Freiling

Mike Freiling

Gentle sunlight

Gentle sunlight

Recent Comments