Kyoto – an elemental city

Text and photos by Jann Williams

Kyoto has a remarkable dimensionality inspired by the elements. In his cultural history of the city, John Dougill conceived Kyoto as eleven different ‘cities’ distinctively epitomising Kammu; Genji; Buddhism; Heike; Zen; Noh; Unification; Tea; Tradition; Geisha and Japaneseness. Elsewhere I have seen Kyoto referred to as the ‘City of Temples’, and now I add ‘the elements’ to this list – for Kyoto is truly an elemental city.

A powerful elemental attraction to Kyoto over the ages has been the allure of the mountains, waterways, and seasonal expressions of the cycle of life exemplified by cherry blossoms and autumn leaves. These have inspired worshippers, writers, artists, philosophers and scholars, and today underpin and nourish the love and passion for the city that residents and visitors experience.

In my exploration of the elements in Japan (see www.elementaljapan.com) references to Kyoto abound. The elements have profoundly influenced the genesis and history of the city and now uniquely define its ambience and modern way of life. Recently joining a flower viewing party (hanami) in Kyoto gave me a taste of the pleasure such intimate elemental activities can bring. Sharing food, drink and companionship under a weeping Sakura next to Fushimi Castle was delightful – highlighting both the ephemeral nature of life and new beginnings.

In this article I draw attention to the more subtle association of Onmyodo, fusui, gogyo and godai with Kyoto. These different expressions of the elements have influenced the look, feel and ‘presence’ of Kyoto as well as many of the festivals, rituals and traditional arts associated with the city. Their contributions to Kyoto’s ongoing appeal are extraordinary and deserve consideration.

The profound connection between Kyoto and the elements begins right at the beginning. Heian-kyo (ancient Kyoto) was located and built according to Chinese Feng Shui principles (Jp: fusui; zoufuu tokusui). These included using the Four Guardian deities, yinyang (Jp: Onmyo, Inyo) and the five Chinese elements (Jp: gogyo) of earth, fire, water, wood and metal to manipulate positive and negative energy patterns in the city. The chosen site for the emergent city was energised by mountains on three sides and the pristine upland waters flowing through the lowlands. Over time fusui has been used in the construction of temples, gardens, palaces and shrines in the city, most recently (most likely) in 1895 (Heian Jingu). It has helped shape the feel of Kyoto to this day, even given modern changes to the city.

As the Imperial Capital of Japan for over 1000 years Kyoto was the centre of Onmyodo – the Way of Onmyo (yinyang). Onmyo and gogyo are deeply intertwined. One tantalising example describes Onmyoji, the masters of Onmyodo, using gogyo in rain making ceremonies at Shinsen-en Garden. The garden is all that remains of Emperor Kammu’s original palace and grounds, built using fusui principles when the capital was moved to Heian-kyo. Although much reduced in size this intriguing garden can still be found just south of Nijo Castle.

The most famous Onmyoji is Abe no Seimei. A Shrine was built for him in Kyoto – by the Emperor no less – after Seimei died in 1005. Seimei Shrine has an active and popular program of events to this day with references to Onmyo and gogyo throughout. The famous Kamigamo Shrine also has many symbols related to Onmyo, the most well known being two cones of sand with pine needles at their peaks. In addition Heian Jingu incorporates ceremonies and symbols that reference Onmyodo and fusui. There are bound to be other examples where this association is found in present day Kyoto.

Godai, the five Buddhist elements (earth, fire, air, water and ether/space), are part of the fabric of Kyoto as well. They can be found represented in many cemeteries in the form of gorinto (in stone) and sotoba (in wood). The imposing five story pagoda at Toji Temple represents these five elements, as do others in Kyoto. Toji dates to the founding of Kyoto when it was constructed as the Temple of the East (the Temple of the West no longer exists). At the time it was the headquarters of Shingon Buddhism, founded by Kobo Daishi – a religion with an intimate connection to the elements. Tendai Buddhism and Shugendo are other religions with a long and strong connection with Kyoto, Onmyodo and the elements. It is a fascinating and compelling story.

These examples provide a glimpse into the elemental city of Kyoto, both physical and metaphysical. For those interested in reading more about the elements in this intriguing and multi-faceted city I invite you to read the essay ‘Kyoto Waters’ by Mark Keane. Blog posts I have written such as Being careful of fire, Zen and the five elements and Time for more tea also address this fascinating dimension of Kyoto – to be found at www.elementaljapan.com.

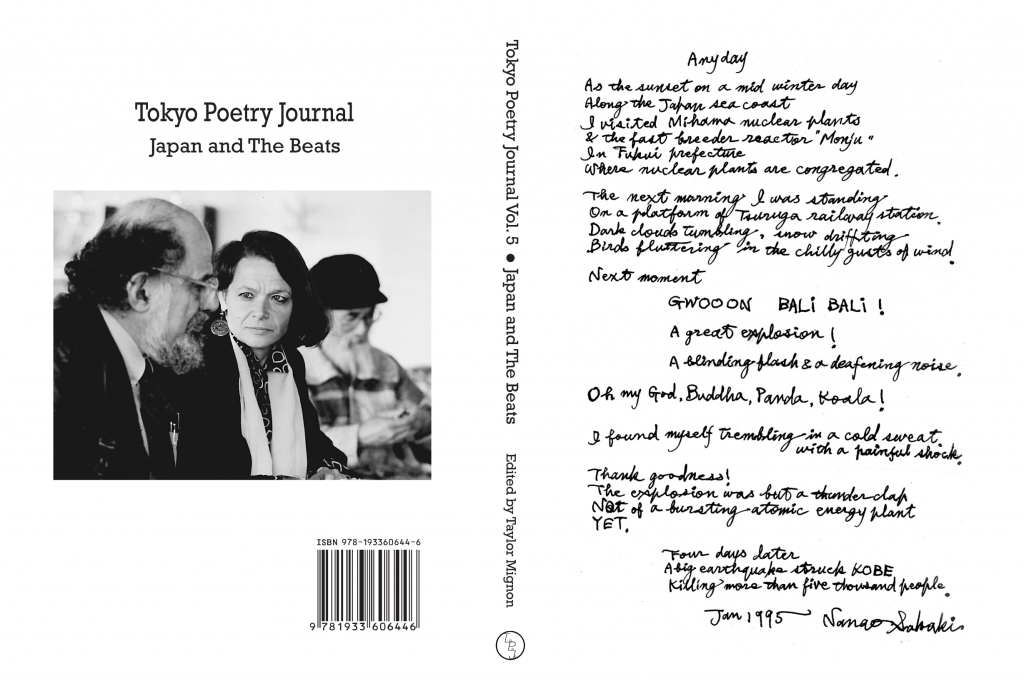

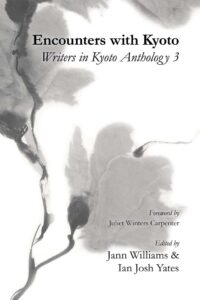

Gateway into the world of Onmyodo – the torii entrance of Seimei Jinja with its lantern pentagram speaking to the five elements on which the Onmyo thinking was based

A lively and informative dinner talk for WiK members was held on March 11 featuring Dutch academic, Mark Teeuwen, who is on leave from the University of Oslo as a research fellow at Kyoto University for six months. His topic was the Gion Matsuri and the politics of heritage. The talk covered the postwar emphasis in Japan on its status as a cultural nation, sparked by a conflagration at Horyu-ji in 1949. This led to such developments as the intangible cultural property and the ‘ningen kokuho’. This was all part of Japan’s self-image as a unique cultural entity.

A lively and informative dinner talk for WiK members was held on March 11 featuring Dutch academic, Mark Teeuwen, who is on leave from the University of Oslo as a research fellow at Kyoto University for six months. His topic was the Gion Matsuri and the politics of heritage. The talk covered the postwar emphasis in Japan on its status as a cultural nation, sparked by a conflagration at Horyu-ji in 1949. This led to such developments as the intangible cultural property and the ‘ningen kokuho’. This was all part of Japan’s self-image as a unique cultural entity.

Recent Comments