Book Review by Rebecca Otowa

Hidden Japan by Alex Kerr (Tuttle, 2023)

The original Hidden Japan was in Japanese, titled Nippon Junrei, and this translation gives us another example of Alex Kerr’s stupendous literary, cultural and linguistic gifts. It comprises a description of journeys in 2017-2019 and is in a way an extension, or re-visitation, of his earlier book Lost Japan (Penguin 2016), also originally published in Japanese. The subtle and complex parts of the Japanese soul — oneness with nature, dark forests, multi-faceted religion, quirky and non-right-angled art — which he is writing about have receded further into oblivion in the years between then and now.

In the introduction to the Japanese book, reproduced here, we are reminded that in Japanese culture, “hidden”, or “back” things are often seen as more mysterious and thus more desirable than “revealed” or “front” things. (The phrase and idea of “in your face” is not easily translatable into Japanese.) He acknowledges his debt to the writer Shirasu Masako and her book Kakurezato (Hidden Hamlets).

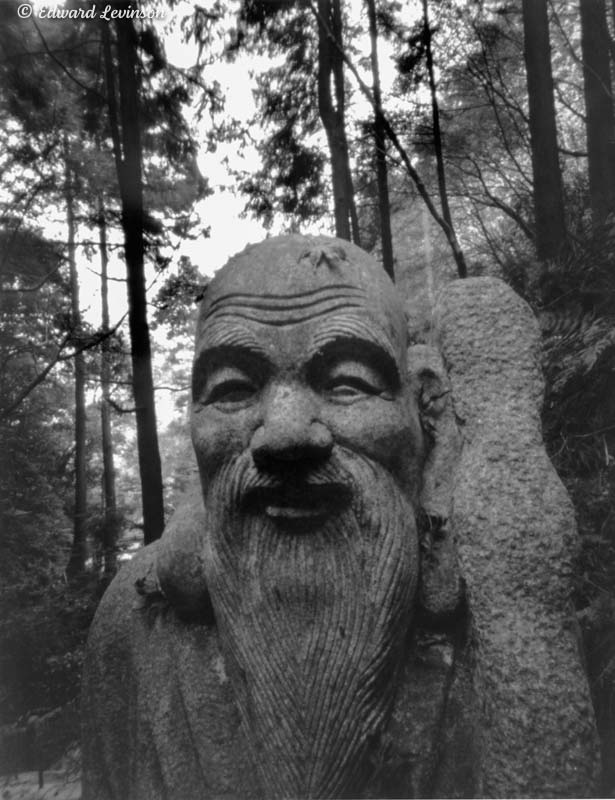

Hidden Japan is a compendium of several trips the author took to ten different parts of Japan including among others Noto peninsula, Amami-Oshima island in the far south, and Yazu and Chizu in Tottori Prefecture. Some are related to his love of old buildings, especially houses, such as his trek to southern Fukushima prefecture; and some are connected to his own history, such as the American Occupation settlements of the Miura Peninsula, Kanagawa Prefecture near Yokohama, where he lived when his father was stationed in Japan in 1965. It also branches out into such areas as trees and tree cultivation, cedarwood shingles in temple and shrine architecture, and the complex origins of the elemental and avant-garde Butoh dance tradition. In a passionate opinion piece modestly titled “Postscript”, Kerr outlines his ideas for “a new philosophy of tourism”, and indeed he has become one of the most important voices for saner policies of tourism in Japan. The book also includes a comprehensive glossary and useful maps.

It’s typical of Kerr’s outlook that he writes in this Introduction, “please enjoy learning about the places in this book. But please never, ever go there.” He quotes Shirasu Masako describing the imperative to share one’s experiences of “hidden” places as “cruel” because it contributes to the place becoming more well-known and more visited, which inevitably changes it and may eradicate the very things that made it charming in the first place. In labeling some places “hidden”, he harks back to the days when people read travel books because they would probably never go to a place, rather than as a preparation for going there. That was the era of the “armchair traveler”. Occupants of the armchairs of those days asked of a travel book that it not only give information about the place described, but also sprinkle in some history, personal adventures, cultural points, and literary worth in the form of quotations and allusions, as well as good writing. Hidden Japan amply provides all these things.

When you read this book, if you find yourself thinking, “I must make that part of my next itinerary”, Kerr implores you to think again. Would the place in question benefit from your visit, or would your presence just make it that much less hidden? Would you be able to refrain from boasting that you had visited one of Japan’s most isolated backwaters, and thus make it likely for friends to visit too? It’s certain that many of these places would benefit financially from a few more visitors. But it is equally certain that many of them, faced with the possibility of a tourist influx, would haplessly destroy the very thing they have set themselves up to be famous for.

As a painful example of this, Kerr mentions the spectacular steep-hilled rice field terraces of Shiroyone, on the Noto Peninsula, which he says “feel a bit staged” because of their close proximity to the cement Michi-no-Eki (“break point on the road”, usually a cement building where local produce and souvenirs are sold). But then he goes oan to say, “Maybe a convenient parking lot right there, with an observation platform from which you can easily snap a shot and then be quickly on your way, is just what people are looking for.” It is certainly what the Chamber of Commerce in this area is looking for, and if we think about various people we know, we could probably think of many who fit neatly into this slot too.

The hidden places that Kerr writes about are certainly enticing, if you seek “the real Japan”, and especially if you like old buildings, nature, and historical associations. It’s very tempting to feel that you are one of only a very few people who have set foot in some isolated locale or other. But especially in these times when “reality” itself is taking a beating as a concept, to be able to say you have “actually visited” some place or other is rapidly losing its meaning. For a second, let’s imagine doing “remote” traveling — sitting comfortably at home and, with such a book in your lap, imagining trekking the mossy paths of Itaibara hamlet, or sampling the fare beneath the grass-grown thatched roof of Mitake-en restaurant, or unraveling the esoteric attractions of Butoh dance as described by a visit to Kami Itachi Museum, to name but a few? Kerr re-introduces us to this type of traveling, done in the mind with one’s imagination as a surprisingly lucid guide. If one is stretching a muscle long disused, all the better. Think of what you are missing — long boring hours in a car or in public transport, all the mundane problems of “getting there”, and most of all, that moment when you finally arrive and are distracted by something else, or inevitably think, “Is this all?” I am reminded of a humour book I once read in which an American, visiting the Louvre, accosted a docent with the question: “Excuse me, where is the BIG Mona Lisa?”

There are many things in this book that fire the imagination, especially if one knows a bit about Japanese history, and one is certain to learn many things that one did not know before. Especially, one learns about the changing attitudes and beliefs of the Japanese people themselves, and how these affected manifestations of culture.

In many ways, though it harks back to a quiet, mysterious country that many want to experience directly though the opportunities get fewer every year, a Japan of the past, Hidden Japan is a book for the future. It conjures up a time when the drive to “go, go, go” to places will be stilled, either by choice or because of dwindling resources or other global contingencies, and we will turn to other means of getting that thrill. At this time of the world, when Covid is relaxing its grip and travel is once more possible, it is a paradox — a travel book that asks, for good reasons, that people not visit the places described. I’m not sure if this was the original object, but it is what I took away from reading it.

Recent Comments